Dissolution of the London monasteries

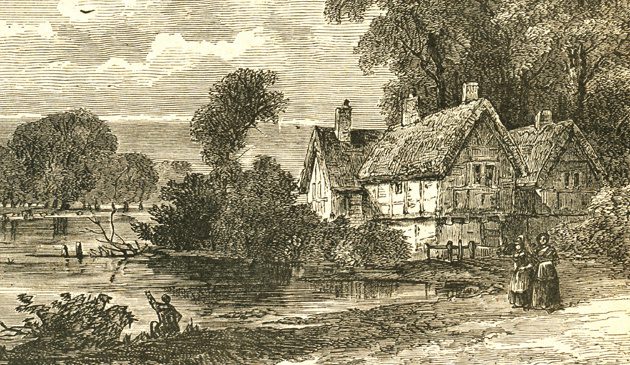

The ruins of the Convent of St. Clare’s at Aldgate, just outside the city wall, in a print published in 1797, more than 250 years after its dissolution. It had been founded in 1293 by the brother of King Edward I and his wife, the Queen of Navarre, and dedicated to St. Clare who had died fifty years earlier at Assisi. The nuns were known as Minoresses and their memory is perpetuated in the street name Minories, which today runs on the east side of the former convent. Part of its grounds later became a farm known as Goodman’s Fields.

For hundreds of years throughout the Middle Ages London’s various monasteries and convents played a significant part in the daily life of the capital. Some of them were large, covering a lot of land, and their monastic churches were a great fixture on the skyline. Several of them acted as London’s hospitals. Many of London’s population lived or worked within them. Their closure in less than a decade, under the orders of Henry VIII, was one of the most momentous changes in London’s history.

In the latter 1520s Henry VIII, who had been a strong supporter of the Pope and the Catholic Church, sought an annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon so he could marry Anne Boleyn. Catherine was the niece of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, however, so it was not an approval the pontiff could easily give. In order to exert pressure Henry appointed reformists to key political and religious posts in England and began passing laws to curb the privileges of the Church. After Pope Clement wrote to Henry in 1531 to give his refusal the King took steps to separate the Church in England from Rome. The Act of Succession of 1534 declared Catherine’s daughter Mary a bastard and confirmed Anne’s daughter Elizabeth as Henry’s heir. A few months later the Act of Supremacy appointed Henry and his successors as the highest authority of the Church in England. Clergy and those in significant positions were required to swear an oath of allegiance, recognising Henry’s authority, with punishment by death for those who refused.

Henry surrounded himself with those who supported religious reform, most notably Thomas Cromwell, who became the King’s chief minister from 1532. They were influenced by the evangelical Protestant philosophy that was arriving from Germany and Switzerland, which opposed monasticism. All monarchs tended to require additional funds and the many wealthy religious institutions were an easy target for their new superior. From 1535 a valuation of Church property took place in order to levy taxes efficiently. The following year it was decreed that all institutions with a gross income of less than £200 would close and their property be taken by the Crown.

One of the most important of London’s monasteries was Holy Trinity at Aldgate. The priory held the Manor of Portsoken to the east of the city wall between Aldgate and the Tower of London. The priors were the only unelected aldermen of London. Having large debts, in February 1532 the priory was forced to surrender itself and its lands to the King and the canons were distributed to other houses. The site of the priory came into the hands of Sir Thomas Audley who, failing to sell the building, had it demolished. Some of its peel of nine bells was sold to Stepney church and others to St. Stephen’s, Coleman Street. Audley built a large house for himself, which was inherited by the Duke of Norfolk, giving the site the name Duke’s Place.

In 1534 Thomas Cromwell settled in a house near Stepney church and devoted his energies to demolishing the religious houses. Richard Layton, former rector of Stepney, was dispatched around the country to investigate abuses and to require monks to swear allegiance to Henry as head of the Church. If they refused the house was dissolved and their property seized. If they accepted, other means were found to dissolve their house.

The Franciscan Friars Observant, particularly those based at Sheen (modern-day Richmond) and Greenwich, had been critical of the King’s marriage to Anne. In 1534 Henry had the entire order closed throughout England and 200 friars imprisoned until they died, probably of starvation. A revolt in the north of England against the religious changes by the King’s “low-born” councillors strengthened Henry’s resolve and the pace of closure of monasteries accelerated during 1536.

Members of the religious orders who resisted the closures could find themselves tortured, and in some cases brutally executed. Those who complied with the King’s wishes and departed their monastic communities were granted a pension by the Crown.

The first to close in the immediate area around London was Elsing Spital for the blind at Cripplegate. John Houghton, the prior of Charterhouse priory, along with two others visited Thomas Cromwell to debate Henry’s supremacy, for which the three Carthusian monks were hanged, drawn and quartered at Tyburn. The remaining members of the Charterhouse community refused to sign the Oath of Supremacy. Four others were executed and nine taken to Newgate prison in 1537 where they were chained upright until they died of starvation. The monastery closed and the building was later acquired by Lord North, a Privy Councillor.

The small and ancient Benedictine convent at Bromley-by-Bow stood where the road out of London crossed the River Lea. It dated back to Saxon times and was possibly contemporaneous with Westminster Abbey but was never an influential or wealthy institution. It was dissolved in 1535 and the land granted to Sir Ralph Sadler, who was later to become Henry’s Ambassador to Scotland.