The original Vauxhall Bridge

Vauxhall Bridge was the first iron crossing over the Thames. This view by Thomas H. Shepherd was published in 1829.

By the end of the 18th century there were three crossings over the Thames in the London and Westminster area. London Bridge, Westminster and Blackfriars had all been built as public works. It is therefore remarkable that in the second decade of the 19th century three new bridges were constructed in quick succession between 1816 and 1819, by private companies incorporated under private Acts of Parliament. Furthermore, the three projects were conceived during a time of war.

The initial Acts of Parliament for the building of Regent’s Bridge and Strand Bridge were both passed in the summer of 1809, each to be financed, constructed, and tolls charged, by individual companies. Both operators commissioned John Rennie as their engineer, who by then had enjoyed a successful career as a designer of docks, canals, harbour and bridges.

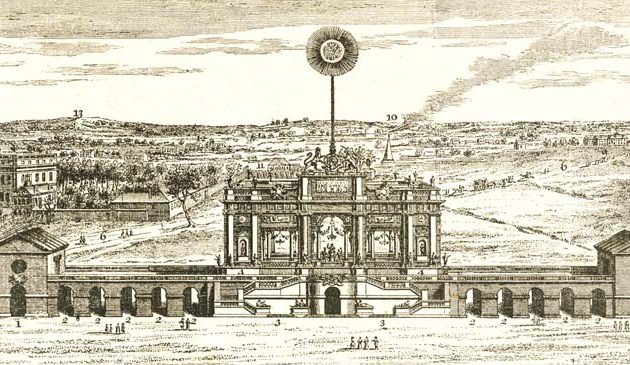

Regent’s Bridge, to be named after the Prince Regent, was conceived as part of a scheme to create new suburbs to the south of the Thames, an area that was little more than fields and market gardens until the early 19th century. The hope was that new suburbs would be formed along an unbroken route, from Hyde Park Corner to Greenwich via Kennington and the Old Kent Road, creating new vehicle and pedestrian traffic to generate tolls. The bridge was planned to cross the Thames between Pimlico on the Middlesex bank and Vauxhall on the Surrey side. It included the creation of a road through Pimlico, which was still largely under-developed at that time. Vauxhall, on the far side of the river, was famous for its pleasure gardens that had been popular as a resort for Londoners since the Restoration period in the mid-17th century.

Rennie’s design for Regent’s Bridge was for an elegant seven-span structure of Dundee blue limestone costing over £200,000. Construction began in May 1811, when the first stone was laid on the Middlesex side by Lord Dundas representing the Prince Regent. However, after work had begun the company ran short of funds. Rennie was obliged to produce a substantially cheaper design of an eleven-span iron bridge, with an estimated cost of £100,000. The company rejected his new design as still too expensive and work was halted. A third version was commissioned from Samuel Bentham, brother of philosopher Jeremy Bentham. The Thames Conservators had doubts about the design of the piers and ordered an inspection by the eminent civil engineer James Walker. Bentham’s design was discarded, and Walker was asked to produce a fourth version. Prince Charles of Brunswick laid the first stone on the Surrey side, over two years after Lord Dundas had laid the first on the Middlesex bank. (Charles’s father, the Duke of Brunswick was to die fighting Napoleon’s army at the Battle of Quatre Bras before the bridge was completed).

The bridge was the first cast-iron crossing over the Thames. The final design consisted of nine equal arches of 78 feet span, on eight rusticated stone and brick piers of 13 feet in width. The length of the crossing was 806 feet, with a carriageway of 25 feet and two footpaths of five and a half feet. The gradient of the bridge was said at the time to be excessive.

Cast-iron bridge-building had been developed during the latter decades of the 18th century. The first of these, Abraham Darby’s famous Iron Bridge over the River Severn at Coalbrookdale, was constructed in 1779. In 1788 Thomas Paine took out a patent on the design of an iron bridge. It was exhibited at Paddington, parts of which were used in the high-level bridge over the Wear at Sunderland. (Paine died in America, having been found guilty and condemned to be executed in Britain following publication of his anti-monarchy book Rights of Man).

Walker’s crossing over the Thames was completed in June 1816, five years after construction commenced. The final cost was £300,000, far in excess of Rennie’s designs. Shortly after its opening it was renamed Vauxhall Bridge due to its proximity to the famous pleasure gardens, and the road leading to it Vauxhall Bridge Road.

In its early days there were few buildings on either side of the crossing other than Millbank Prison on the Middlesex bank, which opened in the same month as the bridge. (The original impetus for the prison was the studies of the aforementioned Jeremy Bentham, begun 20 years earlier, although his ideas were not implemented in the final building). The toll for pedestrians was one penny and up to one shilling and sixpence (18 old pence) for a heavy wagon. The bridge was not patronized as much as had been hoped. There were individual days when crowds flocked to special events at the Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens, although some anyway chose to be carried there by the many available watermen. Vauxhall Gardens promoted the bridge in advertisements, greatly exaggerating the reduction in distance from the West End by using it. They also pointed out it was open all night for pedestrians and coaches, useful for late night revellers.

Income increased from 1838 when the London & South Western Railway created a new line, with its terminus nearby. A decade later, however, the railway was extended to its new terminus at Waterloo and the older station at Vauxhall closed.

The bridge was acquired by the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1879 for £255,000 and became toll-free. The flow of the river had by then weakened the structure. The two central piers were removed, creating a larger central arch. In the following years further strengthening of the foundations was required but the London County Council, successors to the MBW, decided it would be better to completely replace the old structure. Walker’s original bridge was demolished in 1898 and a temporary structure erected while a new crossing was constructed.

Sources include: Peter Matthews ‘London’s Bridges’; John Pudney ‘Crossing London’s River’; John Summerson ‘Georgian London’. David Coke & Alan Borg ‘Vauxhall Gardens, A History’; Walter Thornbury ‘Old and New London (1897); James Elmes ‘Metropolitan Improvements’ (1827).