In brief – Early-Georgian London

By the 18th century London had expanded beyond its walls, linking up with what in the past had been the separate town of Westminster. This detail of the 1720 map by John Strype shows the conurbation stretching from Westminster and St. James’s in the west to Whitechapel, Wapping and Shadwell in the east.

In 1714 Britain entered the Georgian period. London had grown into the largest city and most prominent manufacturing centre in Europe. It was the capital of a growing empire.

Queen Anne had given birth to seventeen children even before she had come to the throne, none of whom survived beyond childhood. It was clear that Anne would inherit the throne but without a successor to follow her. Therefore in 1701, during the reign of her predecessor William III, Parliament had passed the Act of Settlement, which determined that the British Crown would pass to distant Germanic Protestant relatives after Anne’s death. This was to prevent a Catholic monarch. Thus in 1714 the Elector of Hanover became George I of Great Britain, the first of a new dynasty. Father and son George I and II, were first and foremost Hanoverians, both brought up in their Germanic Electorate state and with German as their first language. In their early lives they had been military leaders involved in European conflicts but by the time of their succession to the throne they were relatively elderly and both somewhat distant to their British subjects.

European conflict led to international imperial wars, fought on a number of continents around the globe. Due to its historically strong navy Britain, more than any other nation, eventually benefitted, and by the time of the death of George II had become the world’s greatest international power.

During the Glorious Revolution of 1688 James II had fled to France and continued to live there in exile. Some of his closest supporters followed him, while large numbers of people in Britain – particularly amongst Tories and Catholics – continued in secret to support his return. The supporters of the Stuarts were known as Jacobites and several attempts were made by James and his descendants to win back the throne. The most serious of these came in 1745 when James’s grandson, ‘Bonnie Prince’ Charles, landed in Scotland with a small group of men. From there he marched on London, gaining followers as he went. Having reached Derby he lost his nerve and turned back and, defeated in battle, fled back into exile.

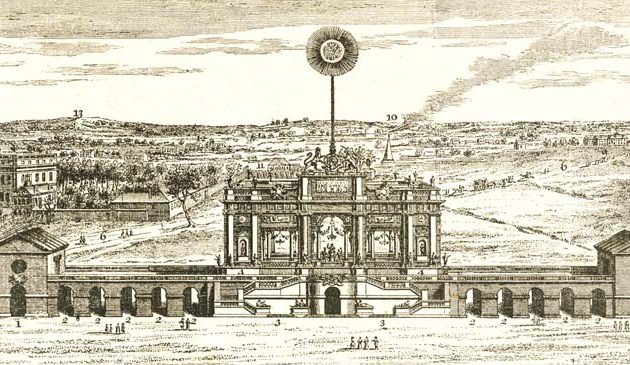

George II had a greater interest in public building than his father and Horse Guards Parade, new Treasury buildings, the Royal Mews at Charing Cross, a new library at St. James’s Palace for Queen Caroline, a house at Kew for their son Frederick, and Westminster Bridge were all created during his reign.

By the early 18th century London had grown to become the largest city in Europe, with a population that passed half a million in the 1740s, amounting to around ten percent of the whole of Great Britain. It was also the largest industrial centre in Europe, particularly for the manufacturing of textiles following the arrival of large numbers of Huguenot silk-weavers in the latter 17th century. London was the capital not just of Great Britain and Ireland but of a growing empire around the world, from the East Indies to the West Indies and North America. It was a trading capital, with by far the country’s largest port. The Thames appeared to be a forest of ship’s masts. Yet London still covered only 10,000 acres, small enough to walk from end to end in an hour or two.