In brief – London in the Age of Improvement

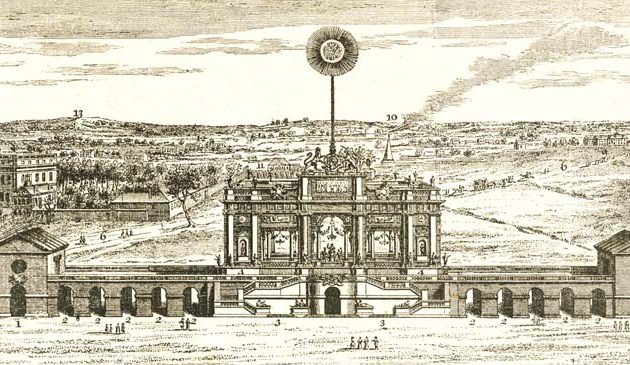

The new Bank of England. It had originally opened on the current site in Threadneedle Street in 1734, at what was then the house and garden of its first governor, Sir John Houblon. It was rebuilt between 1788 and 1833 according to the design of Sir John Soane, shown in this picture by Thomas H. Shepherd from 1827. Soane’s building was largely replaced in the 1920s.

The Regency period brought great changes to the west side of London. The town expanded north and west with a series of new squares. The introduction of omnibuses, and later railways, allowed people to live further than walking distance from their place of work. The introduction of gas lighting illuminated the streets at night. The Metropolitan Police was formed, with an office at Scotland Yard.

Thirty years of peace in the latter half of the 18th century brought a wave of optimism, economic growth and advancements in art and architecture. The Georgian ‘Golden Age’ came to an end with news of the French Revolution and a declaration of war with France.

King George III had reigned for fifty years when he was struck by ‘madness’ in which his mind went into a world of its own and he was unable to carry on his duties as monarch. He remained in that state for a further ten years until his death and during that period his son George, Prince of Wales was his regent, a king in all but name. The Prince Regent lived at Carlton House in Pall Mall, which he had ordered to be extensively rebuilt by Henry Holland.

From the time the Prince of Wales assumed the role of Prince Regent there was a drive for a new magnificence in London. This accelerated further after the Duke of Wellington’s victory at Waterloo that brought a revival in optimism. During the following years a high proportion of the nation’s wealth was spent on new civic projects in London and elsewhere and the period is known as the ‘Age of Improvement’. The result was new palaces in London and Brighton, London’s first university colleges, a major new roadway through the west of London, new bridges over the Thames, new royal parks, a major new waterway, new law courts at Westminster, new churches, new museums and art galleries and new government buildings. It was the most monumental change in London since the 1660s.

The creation of a new park and the grand road southwards from there was one of the most ambitious developments ever undertaken in London. Amongst other things it left us the legacy of Regent’s Park, Regent Street and Trafalgar Square and shaped the West End as it is today. Along with Sir Christopher Wren, the creator of the scheme, John Nash, probably shaped central London more than any other architect.

In 1801 a branch of the Grand Junction canal was opened as far as Paddington and a plan made to create a new waterway from there, parallel with and north of the New Road – today’s Marylebone and Euston Roads – as far as the Thames. When its promoter, Thomas Homer, heard of Nash’s plans in 1811 he approached him with the idea of running the canal through the park. Nash was enthusiastic because he envisaged a charming artificial river that could supply water to an ornamental lake. The initial plan for the Regent’s Canal to pass through the centre of the park was later abandoned and it was relegated to the northern perimeter.