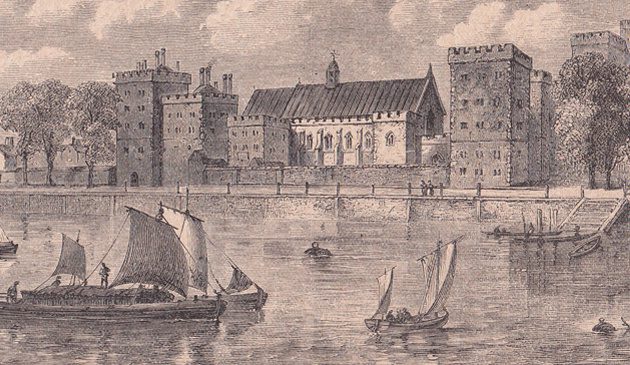

St.Paul’s Cathedral in the early Middle Ages

The shrine of St. Erkenwald at St. Paul’s Cathedral. By the time this engraving was made by Wenceslaus Hollar in the early 17th century Erkenwald’s body had long disappeared. The shrine itself was destroyed in the Great Fire later that same century.

The new building was much larger than its predecessors and so were its grounds, necessitating the re-planning of the western side of the city that had been destroyed in the fire of 1087. Former streets and houses of the parishes of St. Gregory and St. Faith were never rebuilt, or were demolished, to make way. The two parish churches were incorporated into the cathedral to serve the remaining parishioners. (St. Gregory’s was rebuilt onto the south side of the cathedral whereas St. Faith’s took up a space inside the main crypt until 1551). A wall, completed in around 1200, enclosed the cathedral precinct. Following some violent incidents in the 1280s King Edward I gave permission for the Dean and Chapter to enlarge it with gates that could be locked at night.

Inside the north-east corner of the enclosure was the open space of the folkmoot, or assembly ground, where the people of London gathered for collective meetings to discuss civic matters. It was summoned by the ringing of a bell in an adjacent belfry, detached from the main cathedral building. Directly south of the folkmoot was Paul’s Cross from which official royal and city announcements were made from the time of Henry III. The canons’ brewhouse and bakehouse stood to the south, outside the precinct walls, conveniently close to the Thames quays where some of the raw ingredients from the cathedral’s manors could be landed.

A cemetery was located within the precinct, used to bury those with a connection to the cathedral or whose parish church did not have its own graveyard, such as St. Mary Colechurch. When this became full a charnel house was built in the north-east corner of the cemetery, with its own chapel from the 1270s.

The tomb of St. Erkenwald survived the 1087 fire and the relics were translated into the new crypt sometime before 1107. In the following decades there was talk of miracles regarding his tomb and veneration of the saint increased, with his feast day becoming a major event. In 1140, while a new shrine was being created, there was an attempt to steal the remains so they were moved to the chancel and enclosed in a stone tomb. Eight years later that tomb was moved to a more prestigious location behind the high altar, where it remained until the early 14th century.

By the Middle Ages the bishop and canons of the cathedral held large amounts of land in Essex, Middlesex and within London and they provided both rental income and food. The cathedral supported a large hierarchy below the bishop, including the dean (from around 1100), archdeacons, canons and vicars. Not only did they have responsibility for the cathedral itself and its religious duties but also in overseeing the diocese and the direct management of the manors and parishes they held. Their work took them far and wide, including royal and papal responsibilities. It was quite normal for the bishops to simultaneously have important secular roles, such as that of the king’s chancellor. Canons often also acted as clerks in the royal household or as sheriffs, justices and lawyers. Some would have responsibilities in more than one cathedral, such as canon in one and archdeacon in another. Many of the individual religious duties were as a result of, and funded by, endowments from royalty and wealthy citizens. With their work keeping them away from the cathedral for much of the time a great deal of the day to day ecclesiastic and domestic work was normally carried out by resident vicars and secular servants.

St. Paul’s amassed many relics of saints, in addition to the body of St. Erkenwald, resulting in a number of altars and shrines within the building. Religious figures celebrated at the cathedral, some with feast days, included Mellitus, Ethelburga (sister of Erkenwald), and St. Thomas Beckett, as well as his parents who were buried at St. Paul’s.

Bishops of London typically had previously served as a canon at the cathedral. A small minority of canons were of Italian origin, appointed by the popes, but they were not generally popular in London. Some men spent a relatively short period at St. Paul’s during a career that was to bring them from, and take them to, ecclesiastic, academic or secular posts elsewhere.

Until the 12th century priests were often married, and it was fairly common for sons to follow their fathers into careers among the cathedral clergy. Successive prohibitions of clerical marriage, such as that issued by the Council of London in 1129, which was probably held at St. Paul’s, discouraged and eventually ended this practice. From then on, the cathedral canons tended to be the younger sons of the most important and powerful families of London. From that time the lanes surrounding the cathedral became noted as an area of prostitution.

London did not have a university with which the cathedral was associated, as was the case elsewhere such as in Paris. It was nevertheless influential in education and learning and there was a theological school within St. Paul’s from at least the late 12th century. As at most European cathedrals, many of the canons were noted as important scholars and provided administrative and commercial skills to the wider community.

During the 12th and 13th centuries St. Paul’s began to play a part in national celebrations and political events. It became customary when royalty arrived in the city on significant occasions that a procession would enter across London Bridge and pass along Cheapside before arriving at St.Paul’s. That was the case when Richard I arrived in 1194 following his captivity on the Continent during the Crusades or when Edward I finally arrived in England for his coronation in 1274, two years after the death of his father. The cathedral was also used as the location for a number of important national assemblies, either inside the building or in the churchyard.

Westminster Abbey developed as the place of coronations, royal weddings and funerals; St. Paul’s where the monarchy would meet the citizens. It was at St. Paul’s that Prince John and the citizens deposed the absent King Richard’s unpopular representative William Longchamp in 1191. After John ascended the throne St. Paul’s became the focus of many of the major events during his reign, such as when for a brief period he resigned the crown in favour of the Pope, or when the barons brought Prince Louis of France to England to succeed John. The cathedral played a significant role during the tumultuous reign of his son Henry III. Following his defeat at the Battle of Lewes in 1264 the King was held captive in St. Paul’s while the barons formed a parliament at Westminster.

Sources include: Various ‘St. Paul’s – The Cathedral Church of London’; Christopher Brooke ‘London 800-1216’; John Schofield ‘London 1100-1600’; Caroline Barron ‘London in the Later Middle Ages’. Illustration courtesy of the collection of Hawk Norton. With thanks to Olwen Maynard for fact-checking.

< Back to The founding of St. Paul’s Cathedral

Forward to St. Paul’s Cathedral during the Reformation >