In Brief – Saxons, Vikings and Normans

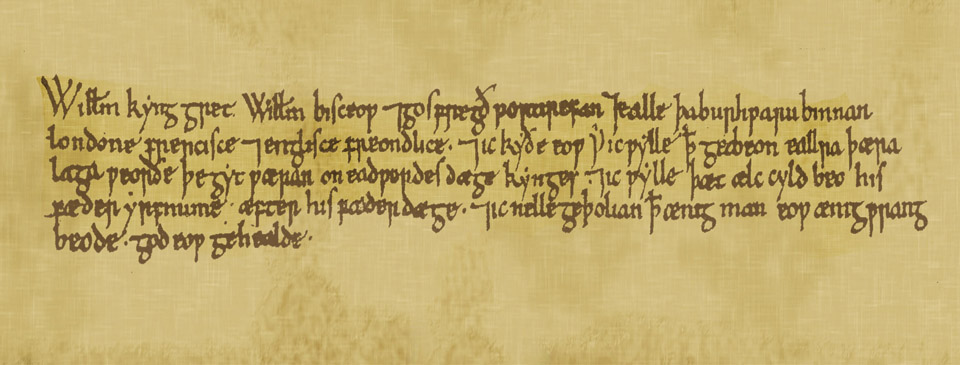

The text of the charter of reassurance issued to the people of London by William the Conqueror shortly after his coronation.

Another claimant was the baron William of Normandy and Harold was famously slain at the Battle of Hastings, bringing an end to the line of Saxon kings. Following the battle Harold’s body was buried at Waltham Abbey, to the north of London. William moved on London but found it too heavily defended and marched his troops on to Winchester. Returning back east on the north side of the river he established himself at Westminster Palace from where he orchestrated negotiations with London, finally entering the city in December. William was crowned King of England at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day 1066. Thereafter William generally held court at Westminster for the great feast of Whitsun when he would entertain the leading barons and clergy of his lands.

Three stockades were built around the edge of the city in case of uprising from London’s population. Two, on the west side, were built and occupied by Norman knights. The third, outside the south-east side was constructed on William’s orders as a royal castle and that became the Tower of London. He guarded himself against uprising but also required the allegiance of the town’s population. As a result of negotiation by the Bishop of London the King issued a charter of reassurance to its occupants soon after his coronation.

Despite the conquest, life in the city continued more or less uninterrupted as before. England became a part of an enlarged Anglo-Norman empire. Although the majority of the city’s population, which numbered around ten or fifteen thousand, were Saxon it was a very cosmopolitan town where Normans, French, Norwegians, Danes, Germans and Flemings mingled. William additionally invited to London a community of Jews from Rouen in Normandy.

Once again London was conveniently placed between the king’s Continental and English lands, and well-positioned to take advantage of shipping routes. Wharves were created along London’s riverbank, with a new parallel riverside road, the modern-day Upper and Lower Thames Street.

After ten years on the throne William’s son, William Rufus, ordered the construction of a great new hall as an extension to the Palace of Westminster and it was completed in time for him to hold court there at Whitsuntide 1099. By the standards of the day the great Westminster Hall was a vast building, certainly the largest hall in England and possibly the whole of Europe. The Court of Exchequer, responsible for the accounts of the Treasury, began to conduct its business from the Great Hall, with its clerks housed close by.

In the first half of the 12th century an important new charter was granted to London by the king, marking an important early step in the city gaining the rights of self-government and other freedoms.

Three major religious houses were founded during the reign of Henry I. His wife, Queen Matilda, established the order of Holy Trinity, Aldgate and it remained the leading monastery within the city walls throughout the early medieval period. Matilda was also responsible for the foundation of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, to the north-west of the city walls and perhaps the country’s earliest hospital for lepers. Another major religious house throughout the Middle Ages was St. Bartholomew’s at Smithfield, originally founded by Rahere, a jester to the royal court of Henry I.

Once again the crown was contested after the death of Henry, leading to civil war in which London backed the eventual winner, King Stephen, the last of the Norman kings. By the end of the Norman period London, with its royal neighbour of Westminster, was again an important and thriving town. Yet it was only one of a number of such in the Anglo-Norman empire and could not yet consider itself as a capital.

With thanks to Ursula Jeffries for help with fact-checking and proof-reading.

< Go back to In Brief: Roman London or forward to In Brief: London in the early Middle Ages >