London’s first underground railway

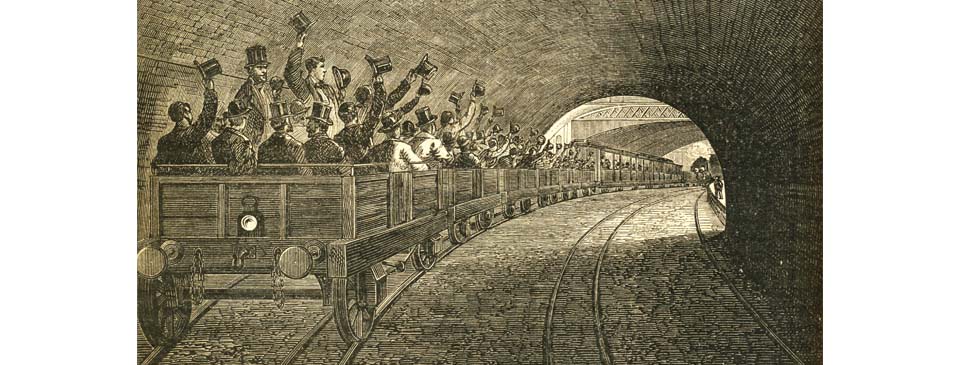

The image shows VIPs on a demonstration run on the Metropolitan Railway, perhaps prior to its opening. The carriages behind the locomotive are first-class while those at the back, in the foreground, are probably third-class. The train is running on the broad-gauge rails of the Great Western Railway. An inner rail can be seen, allowing standard gauge trains of the Great Northern and other companies to use the line.

A major feature of the Metropolitan would later become its extension far out into the Buckinghamshire countryside. It began modestly with a short single-track branch line from Baker Street to Swiss Cottage, with intermediate stops at Marlborough Road and St. John’s Wood, the latter important for Lord’s cricket ground. At that time Swiss Cottage was still in the countryside and passengers alighting there could enjoy the scenery. It was initially owned by a separate company and named the Metropolitan & St. John’s Wood Railway, opened on Easter Monday 1868.

A committee of the House of Lords recommended in 1863 that the underground railway system should be extended south to the Thames and to create an ‘inner circle’. To achieve this the District Railway was formed, which was to gradually create the southern part of the circle. For their part, the Metropolitan opened a new section in October 1868 from Edgware Road to Praed Street, serving the GWR’s Paddington station, and then through the sparsely-populated districts of Bayswater and Notting Hill Gate, and on to Kensington, and Brompton (Gloucester Road).

The Great Eastern Railway moved its London terminus from Bishopsgate at Shoreditch into the City at Liverpool Street, opening in stages between 1874 and 1875. That prompted the Metropolitan Railway to extend their line the short distance from Moorgate to Liverpool Street, where their Bishopsgate Street station connected to the GER’s terminus. In 1878 the line was extended further to Aldgate after pressure from the City of London Corporation.

It became clear that the Metropolitan Railway had been paying too much in dividends in its first years and wasting resources, leaving it short of capital. They were also finding that tunnelling under expensive conurbation was not profitable and thereafter much of its future expansion was to be overground through countryside. The St. John’s Wood branch was extended in July 1879 to Finchley Road and West Hampstead. Harrow on the Hill was reached in August 1880.

Over a decade after the parliamentary committee recommended the creation of an inner circle it had still not been completed. The company was finally forced to act when Parliament approved a rival plan from a group of businessmen. It spurred the Metropolitan and District companies to cooperate, at least to the extent of competing the circle. Together they persuaded the Metropolitan Board of Works and the Commissioners of Sewers to contribute to the cost of completing the circle. A Bill was passed in 1879 to extend the Metropolitan as far as Tower Hill, with a spur to Whitechapel where it connected to the East London Railway. In September 1882 an extension was completed to a station named Tower of London, where a rickety wooden booking office was erected that lasted for almost 60 years. It then took a further two years, and at great cost, for the Metropolitan to complete the final link, from Tower Hill to Mansion House. Trains began running around the full circle line in October 1884. Agreement between the two companies was that the Metropolitan ran trains clockwise and the District anticlockwise.

The Metropolitan railway was the forerunner of what was to become a major underground rail network beneath London. Yet in its earliest decades it was connected to mainline overground services that provided through trains to numerous stations around the south-east of England.

At the start of the 19th century, before the introduction of affordable public transport, workers could only walk to their place of employment. From the 1830s omnibuses allowed more rapid commuting over longer distances. Railways could move people even faster and further, providing greater choice in where they lived, perhaps somewhere cheaper or more pleasant. Overground railways could bring people to London but the Metropolitan provided the final link to bring them to their place of work in the City. Not only did the Metropolitan make it quicker and easier to travel around but it generated its own business by changing where people lived and worked in proximity to stations. That fuelled the creation of new suburbs and physical growth of London.

The Metropolitan Railway remained independent until it was integrated into the London Underground network when the London Transport Passenger Board was founded in July 1933.

Sources include: G.A. Sekon ‘Locomotion in Victorian London’; Christian Wolmar ‘The Subterranean Railway’; Christian Wolmar ‘Cathedrals of Steam’; Jerry White ‘London in the 19th Century’.