London’s Jewish Community in the 19th century. Part 2 – Their lives

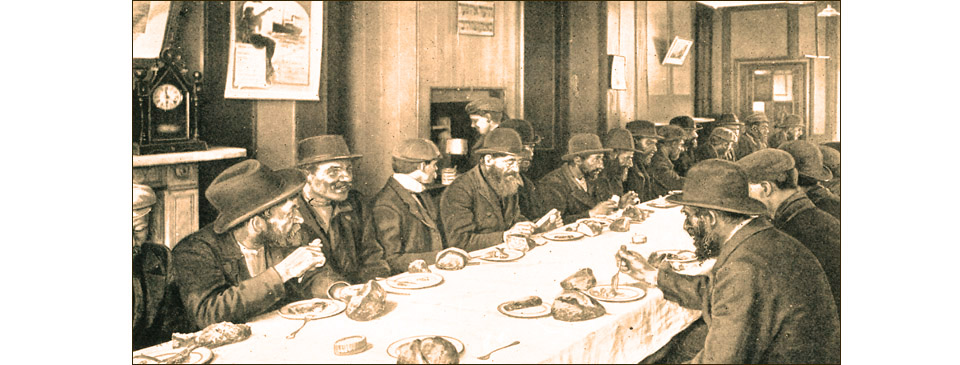

Newly-arrived men are provided with a frugal meal at the Poor Jew’s Temporary Shelter in around 1885. It began in Church Lane, Whitechapel. Sir Samuel Montagu and others took it over and provided a building in Leman Street to give a home for new arrivals for up to two weeks. It eventually sheltered up to 4,000 immigrants each year.

Jewish radicals attempted to create a socialist movement in the 1880s, with the Yiddish newspaper Arbeiter Freind (Workers Friend) as its mouthpiece. Based in Commercial Street, it continued publication until the First World War. The socialists’ meeting place was at 40 Berner Street at Whitechapel (later re-named Henriques Street) and William Morris was a frequent visitor.

Unions were formed for various trades, renamed, merged with other unions, or disappeared altogether. In 1896 there were at least thirteen, possibly more. These were largely independent of those being formed by their Gentile counterparts, due to cultural, religious and language differences. Membership was low and few had more than 300 members at any time. Yet there was a growing militancy among garment workers and there were sporadic small strikes. At the same time a House of Lords commission on the state of sweatshops concluded they were a “disgrace to a civilised country”. In March 1889 2,000 workers marched to the Great Synagogue in support of an eight-hour working day. Strikes began to break out in the larger workshops and several months later a strike took place involving 10,000 workers, with the (then) modest demand of a twelve-hour working day. After weeks of campaigning and negotiation, with arbitration from Sir Samuel Montagu, most of the strikers’ demands were met. A new wave of Jewish immigrants joining the pool of workers soon undermined the agreements.

The East End ghetto wasn’t all hard work and melancholy. There was also playfulness and joy: laughter during a Yiddish play; joyous klezmer music; the chatter of Jewesses at their doorsteps; youths playing cricket at Bell Lane and Frying Pan Alley at Spitalfields; Jewish weddings; bar and bat mitzvah celebrations when boys and girls came of age; and festivals such as Pentecost, the Feast of Tabernacles, and the carnival atmosphere prior to Passover.

During the period from 1870 until the early 20th century 120,000 Jews settled in England. In the 44 years from 1870 to 1914 the number increased from 60,000 to a quarter of a million, through immigration and a natural increase. By then, London contained more East European Jews than any city in the world other than New York and Chicago.

As early as 1886 it was suggested within the Jewish community that the government should limit immigration, but it was a controversial idea. Benjamin L. Cohen, Unionist MP for Islington, offered to assist the anti-alien lobby in Parliament in the creation of such regulations. In the early 20th century anti-alien opinion was growing within the general population, particularly concerning Jews, and it was then Britons who were calling for limits on immigration. There was a severe recession in the early years of the century and some used the Jews as a scapegoat for the country’s woes. Home Secretary Aretas Akers-Douglas said that Jews were willing to work for starvation wages and live in conditions that no “decent British man” would tolerate and claimed that the “whole of the native English population was being pushed aside and turned out of dwellings.”

A significant figure in the anti-Jewish sentiment was Major William Evans-Gordon, Conservative MP for Stepney, supported by other East End MPs. There were some vastly exaggerated claims of the number of Jews entering the country and talk of the country being swamped with immigrants, taking away British jobs. In reality, between 1871 and 1910 there were more Britons emigrating to America, Canada, Australia and New Zealand than immigrants arriving. After much debate, in 1905 the Conservative government passed the Aliens Act, which restricted entry into the country. It only applied to ships bringing more than 20 immigrant passengers so had little effect. The anti-Jewish sentiment lasted until the media, MPs and then the population, instead turned its attention to Germans in Britain in the lead-up to the First World War.

The Jews of Whitechapel worked hard and had children and grandchildren who made a significant contribution to British life. Marcus Samuel from Whitechapel founded the Shell oil company. The Hackney stall-holder Jack Cohen went into partnership with T.E. Stockwell and they used their abbreviated names for their Tesco stores. Chaim Reeven Weintrop from Whitechapel used the stage name of Bud Flanagan, becoming a famous comedian and singer. Isaac Belisha became Minister for Transport and left us with the belisha beacons at zebra crossings. Isadore and Montague Gluckstein founded the Lyons tea shops. These are just several of many notable children of Jewish immigrants.

The newly-arrived people, or their children, learnt English, found higher income employment, and moved away from the ghetto. But wherever they moved they stayed close to others of their community, forming concentrations in various suburbs in North and North-East London. Many moved to the leafier Stamford Hill where they formed a new Jewish quarter of Ultra-Orthodox Jews. Others Anglicized and moved up the social ladder to Ilford, Redbridge, Golders Green, Hendon, St. John’s Wood, Maida Vale, Hampstead, Highgate and other salubrious suburbs. In the 20th century many assimilated into mainstream British life and Jewishness increasingly became a secular identify for them rather than a religious observance. The Whitechapel district continued as a bustling area, with the Jews making way for the next wave of immigrants. Those were the Bengalis from Bangladesh, who took over the residential streets and the textile workshops, opening mosques in place of synagogues.

Sources include: Lloyd P.Gartner ‘The Jewish Immigrant in England 1870-1914’; Robert Winder ‘Bloody Foreigners’; ‘Living London’ ed. George R. Sims (1902); Panikos Panayi ‘Migrant City’; John Marriott ‘Beyond the Tower’; Walter Besant ‘East London’ (1903); Millicent Rose ‘The East End of London’ (1951); Chaim Bermant ‘London’s East End – Point of Arrival’, William Velvel Moskoff and Carol Gayle ‘An Immigrant Bank in Philadelphia Serving Russian Jews: The Blitzstein Bank (1891–1930)’ (paper).

< Back to London’s Jewish Community in the 19th century. Part 1 – Their arrival