The Great Exhibition and the Crystal Palace

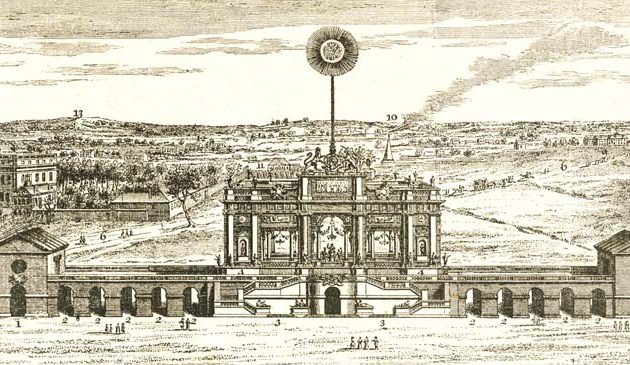

Flags of every nation flew from the top of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park throughout the duration of the Great Exhibition. Here we see the transept of the great glass hall. Carriages line up on South Carriage Drive as passengers arrive.

There was a period of indecision and confusion as various ideas and architects were considered and rejected by the commission. Nearly 250 plans for a building were submitted from British and foreign architects. Brunel submitted a design that required fifteen million bricks and was dominated by a dome larger than St. Peter’s in Rome. It would have been very expensive to build, would take too long, and met with public scorn. There was objection regarding elm trees that would have to be felled, prompting Punch to quip:

Albert! spare those trees,

Mind where you fix your show;

For mercy’s sake, don’t, please,

Go spoiling Rotten Row.

While this was taking place, in June 1850 the gardener Joseph Paxton was visiting the House of Commons on business and came into conversation about the exhibition building. The Board of Trade informed him they were still searching for a design. Paxton was the son of a Bedfordshire farmer. He had come to the attention of the Duke of Devonshire while working as an under-gardener for the Horticultural Society at Chiswick and was appointed as Head Gardener at Chatsworth. There he created the Great Conservatory, covering an acre of ground. He continued designing glass houses and buildings on the Duke’s other estates. By 1850 he had been designing glass houses for twenty years. Queen Victoria described him as the “ordinary gardener’s boy” but the Duke of Wellington remarked: “I would have liked that man to be one of my generals”.

Hearing of the continuing search for a suitable design Paxton visited Henry Cole and learnt of the requirements for the building. While sitting at Derby railway station on his way home he made a sketch on a sheet of blotting paper. A few days later he returned to London with plans for a gigantic glass hall he had drawn up, with the assistance of the engineer of the Midland Railway. By chance, on the same train was Robert Stephenson, who thought highly of what he was being shown. Stephenson took the plans to the Royal Commissioners. Various meetings were held to modify the plans and Brunel provided Paxton with good advice, despite the rejection of his own design. To further his case, Paxton sent a copy to the Illustrated London News who subsequently published a picture of his draft design. The engineer John Henderson later proposed adding a transept, which provided strength to the building but also vastly improved the appearance. The glass hall allowed for the elm trees to remain inside the building. After some reservations, the idea was accepted by the Commission.

The writer Douglas Jerrold had visited Paxton at Chatsworth in 1849. Nevertheless, in July 1850 he wrote sarcastically in Punch magazine about the (then) proposed glass hall for the exhibition, under the pen-name of Mrs. Amelia Mouser: “…a palace of very crystal, the sky looking through every bit of roof”. The description of “a palace of very crystal” was frequently quoted in newspapers until the building had become widely known as ‘The Crystal Palace’.

The exhibition was funded by raising subscriptions, with the Duke of Wellington heading the list of subscribers. Towns around the country subscribed a total of £75,000. The government provided assistance but not funding.

Construction of the glass building was overseen by Matthew Digby Wyatt who had previously assisted Brunel on the construction of Paddington Station. Charles Fox and John Henderson of Birmingham undertook the work and retained ownership of the structure, renting it to the Commission at a low rate. The ground was levelled in August and September 1850. Concrete foundations were laid with 34 miles of pipes to which eight-inch diameter iron columns could be bolted. By December 2,000 workmen were working on the construction. Standardized, interchangeable, mass-produced components, use of steam-driven machines, and division of labour allowed for rapid assembly and disassembly. Paxton noted how three columns and two girders could be erected in just 16 minutes. Eighteen thousand panes of glass could be fixed each week. Instructions could be transmitted by telegraph and material quickly delivered by railway. Machines to perform certain tasks were specially designed and created. Hardly any scaffolding was used.

The building was 1,848 feet long (over a third of a mile) and 408 feet wide, twice as wide as St. Paul’s Cathedral and almost four times as long. The main building rose in three stages tall along its length, with the highest level at 64 feet above the ground. A central transept rose to 108 feet high. The building covered 18 acres and enclosed thirty-three million cubic feet of space. There was nearly a mile of galleries, with stairways leading to upper galleries. The building comprised 900,000 square feet of window weighing 400 tons, supplied by Chance Brothers of Smethwick who had earlier introduced into Britain the method of producing sheet glass. Three thousand five hundred tons of cast iron and 550 tons of wrought iron were used to make the thousands of columns, trellis girders, trusses, guttering, and 202 miles of sash bars. The transept arch was formed of 16 semi-circular ribs of laminated timber. Timber flooring was laid throughout. A boiler house supplied steam through underground pipes to drive moving machinery and smaller pipes supplied the fresh water for fountains. Five hundred painters were employed, using colours chosen by decorator Owen Jones.

Such was the scale of the enterprise that London’s streets, especially those leading from the railway termini and docks, were jammed with wagons piled high with packing cases, or laden with machines, in the days and weeks leading to its opening. Up to 100,000 people gathered each day to watch the building take shape. An entry of five shillings (25p) was charged for entry to the site, with the proceeds placed in an accident fund.

The work took nine months and was completed on time. The Times wrote:

Not the least wonderful part of the Exhibition will be the edifice within which the specimens of the industry of all nations are to be collected… It took 300 years to build St. Peter’s at Rome, and thirty-five to complete our own St. Paul’s. The New Palace of Westminster has already been fifteen years in hand, and is still unfinished… Not only was [the Crystal Palace] to rise with extraordinary rapidity, but in every other respect is to be suggestive of ‘Arabian Nights’ remembrances.

In his memoirs, the eighth Duke of Argyll wrote:

As a spectacle of joy and of supreme beauty, the opening of the Great Exhibition of 1851 stands in my memory as a thing unapproachable and alone. This supreme beauty was mainly in the building, not in its contents, nor even in the brilliant and happy throng that filled it. The sight was a new sensation, as if Fancy had been suddenly unveiled. Nothing like it had ever been seen before… its loftiness, its interminable vistas, its aisles and domes of shining and brilliant colouring.