The Great Exhibition and the Crystal Palace

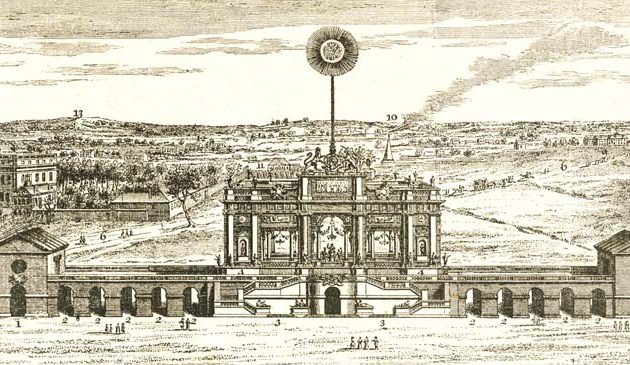

Flags of every nation flew from the top of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park throughout the duration of the Great Exhibition. Here we see the transept of the great glass hall. Carriages line up on South Carriage Drive as passengers arrive.

Unprecedented numbers of people came to see the exhibition and it would remain as the most popular event in London for the following century. The roads leading to Hyde Park were fully congested for the two weeks after the opening. There was initially great fear of unruly mobs running riot, for which London had much previous experience. The Duke of Wellington arranged for 10,000 troops to be on stand-by and the Metropolitan Police recruited an additional thousand constables. In the event, there was no trouble. The Queen made many visits during the course of the exhibition and wandered around without protection.

The cost of entry was one pound on the second and third days, then five shillings thereafter. Entrance was reduced to one shilling from 26th May to allow everyone a chance to visit. Over six million entries were made during the exhibition’s 140 days between May and October, with around four million individual visitors. The largest daily attendance was just before it ended, when 109,760 visited within one day.

A Working Classes Central Committee had been formed to promote the exhibition to working men and women in a positive way. Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray and other prominent people were members. People arrived from all over the country and beyond. That would not have been possible without the network of railways that had developed in the preceding decade. Special trains were run within Britain and the South Eastern Railway operated a special daily cross-channel service from France. Individuals pawned their silver watches to raise money for railway agent Thomas Cook’s excursions to London. Local clubs were created to arrange journeys and negotiate cheaper fares. Entire parishes of country-folk arrived, with men in their smock frocks. Vicars escorted their parishioners, soldiers by their colonels, sailors by their captains, school-children by their teachers. Proud exhibitors sent their workpeople to see their machinery and other products on display. Queen Victoria wrote of Mary Callinack, a “most hale old woman” aged 85 who had walked all the way from Penzance with her belongings in a basket on her head. The Lord Mayor gave Mary a sovereign for a return journey.

Catering within the Crystal Palace was put out to tender, which was won by the Schweppes beverage company, who paid £5,500 for the right. They in turn sub-contracted to two other companies but, as well as selling their existing sodas and lemonades, used the exhibition to launch mineral water from their new factory at Malvern. Over a million bottles of the latter were sold during the course of the event. They made a profit of £45,000.

London’s Omnibus employees worked seventeen-hour days to cope with the increase in passengers. The Daily News complained of exorbitant fares being charged, of refusing passengers of less than the highest price, and the insolence of the omnibus staff. There were greater numbers of people arriving in London than existing hotels and boarding houses could accommodate and prices rose accordingly. People took in lodgers. A vast temporary hotel was created at Pimlico, sleeping 1,000 people per night.

The Great Exhibition was a tremendous success. In his Household Words Charles Dickens wrote of the oversees visitors: “Altogether I think that a little peace, and a little good-will, and a little brotherhood among nations will result from the foreign invasion”. But it had to end, much to Victoria’s disappointment. On the final day she walked through the entire building and wrote: “It looked so beautiful and I could not believe it was the last time I should behold this wonderful creation of my beloved Albert’s”.

The Great Exhibition lasted for five months and eleven days. The closing ceremony on 15th October was attended by Albert but not Victoria. A week later the Queen knighted Paxton, Cubitt and Fox for their efforts. The Executive Committee of the exhibition, and the Lord Mayor and aldermen of the City, were all invited to Paris by Louis Napoleon for the week-long ‘les fêtes anglo-parisiennes’. Events included a banquet at the Hôtel de Ville, a reception hosted by Napoleon at St. Cloud, a fête at the British Embassy, a review at the Champs de Mars, and a performance at the Théâtre Français, including a ballet entitled Crystal Palace.

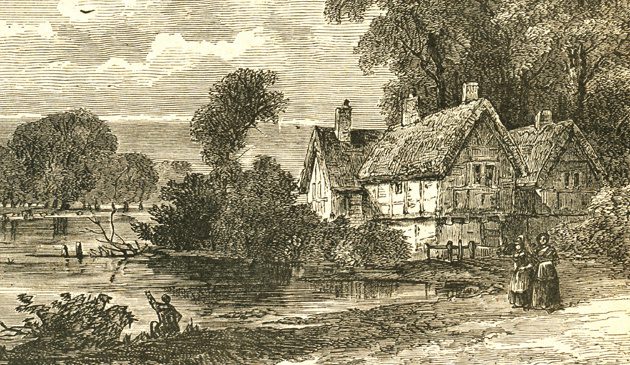

Many publications were inspired by the Great Exhibition. Amongst them, Henry Mayhew and the cartoonist George Cruickshank produced the humorous comic novel 1851: or, The adventures of Mr and Mrs Sandboys and family, which tells the story of the family’s attempt to travel to the exhibition from Cumberland. After many misadventures they finally arrived after the event had finished. One illustration showed Manchester completely deserted because everyone had left for London. The image of London, however, shows an overcrowded city.