The Great Exhibition and the Crystal Palace

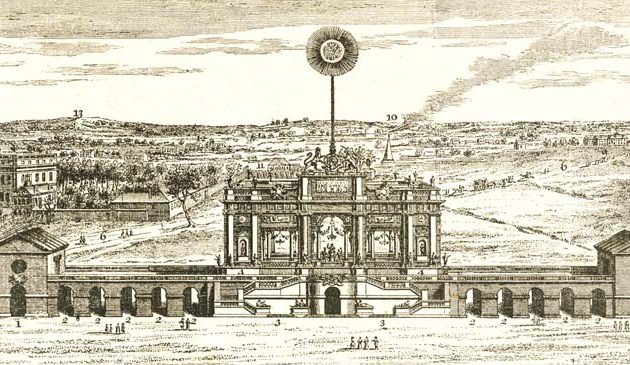

Flags of every nation flew from the top of the Crystal Palace in Hyde Park throughout the duration of the Great Exhibition. Here we see the transept of the great glass hall. Carriages line up on South Carriage Drive as passengers arrive.

It was Prince Albert’s mission to bring together different strands of industry and the arts to improve technical innovation and design, as was already happening in France. To achieve this, his aim was to create a centre for the improvement of design in industrial products. Brompton, to the south of Hyde Park, was still largely rural so 87 acres of land was purchased using the profit from the exhibition. But Albert died in December 1861 at just 42 so never lived to see South Kensington, as it was re-named or ‘Albertopolis’ as it was unofficially known, transform into a district of museums, colleges, and the Royal Albert Hall. A memorial to the Prince was built in Kensington Gardens, facing the hall from across the street. The 54-metre-tall Albert Memorial contains a sculpture of Albert holding the catalogue of the Great Exhibition.

Despite initial scepticism, the Crystal Palace building had proved to be hugely popular and many wanted it retained. From the outset, however, it had been agreed it would be removed from the site within seven months of the end of the exhibition. Various ideas were put forward for a new home, including Regent’s Park, Kew Gardens and the new Battersea Park. A public company was formed by Samuel Laing and Leo Schuster, both directors of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway, and with Paxton as a director. The building was then purchased from Fox and Henderson for £70,000. The Crystal Palace Company dismantled, moved, and re-erected it on Penge Peak, straggling Sydenham and Penge in Surrey to the south-east of London. It stood within 200 acres of estate owned by Schuster. Paxton re-used the materials from the original building but re-designed it as a larger structure, with twice as much cubic space. Two smaller side apses were added and there was a new barrel-vaulted roof running the length of the building. Brunel designed water towers to supply fountains, cascades, and lakes. The newly rebuilt Crystal Palace, with its surrounding gardens, was opened by Queen Victoria in June 1854.

The company’s intention was for it to become the centre-piece of a new pleasure garden. A railway branch line from the London to Brighton railway was created to bring visitors, and a further line opened in 1865. As at similar pleasure gardens, entertainments at Crystal Palace were arranged to draw in the crowds but the ambition was for events to be of a more high-brow nature than elsewhere, described by the company as “refined recreation, calculated to elevate the intellect, [and] instruct the mind”. The great glass building contained many cultural exhibits, including Egyptian, Roman, medieval, Elizabethan and industrial courts. There were reproductions that included the Elgin Marbles, part of the Alhambra, and frescoes from the Vatican. A series of dinosaur sculptures was commissioned for the surrounding park, designed by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins. From 1857 a Handel festival was held every three years with a vast choir and audiences of thousands. The company formed a cricket club, which in 1861 was extended to play football. Two years later it became one of the founding member clubs of the Football Association. A stadium was built in the park, which hosted the FA Cup Final between 1895 and 1915. The current Crystal Palace Football Club was founded as a professional team in 1905.

In those early years, visitor numbers were high, amounting to over fifteen million in the first decade. Yet as time went on it was necessary to introduce more populist attractions such as fireworks, a circus, and pet shows in order to keep visitors coming. Ticket prices were regularly reduced. The Crystal Palace building was destroyed by fire in November 1936 but the surrounding park remains, including the dinosaurs. The area still retains the name of Crystal Palace.

Sources include: Eric de Maré ‘London 1851’; Edward Halford ‘Old & New London’ (1897); Jerry White ‘London in the 19th Century’; John Richardson ‘Annals of London’; Neville Braybrooke ‘London Green’ (1959); Alicia Amherst ‘London’s Parks and Gardens’ (1907).

< Back to London during the mid-19th Century