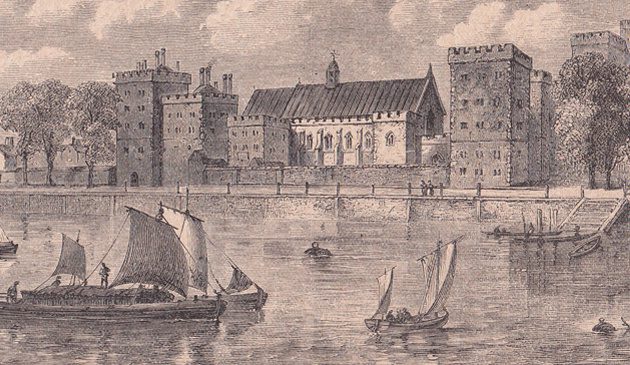

The medieval Westminster Abbey

In an attempt to add to the prestige of Westminster Abbey Henry III acquired from the Patriarch of Jerusalem a crystalline reliquary of Christ’s blood, together with a letter of authentication. On St. Edward’s Day 1247 Henry carried the reliquary from St. Paul’s Cathedral to Westminster Abbey, dressed in a humble cloak, and in procession with all the priests of London. The monk Matthew Paris, who witnessed the procession, recorded it in his manuscript Chronica Maiora, a detail of which is shown here.

It was from Henry’s time that the abbey gained revenues from royal and aristocratic legacies to finance commemoration of the anniversaries of their deaths. Henry granted the right for the abbey to hold two major fairs each year in St. Margaret’s Churchyard, in January to commemorate Edward the Confessor’s death and in October for the feast of his translation. The two fairs were combined into one lasting 32 days from 1298.

Henry had intended for the work to be finished by 1255, but that was prohibited by the costs and scale of the work. The quire was complete in 1269. On the Feast Day of St. Edward in October of that year the consecration ceremony took place and the body of the saint moved to its new tomb. As Henry had wished, the shrine of Edward became a place of pilgrimage throughout the Middle Ages. There were stories of miracles occurring and some sick people would sleep around it in the belief that their close proximity could lead to a miracle cure.

Henry died in 1272 and a magnificent funeral was held in the abbey. His son Edward was at that time in the Mediterranean on a crusade and did not return to England for another two years. Edward and Eleanor of Castile’s coronation at the abbey was the first of a king and queen together.

Over a decade after Henry’s death work on the abbey had only been completed to the end of the quire. He left instructions in his will for Edward to finish the western part of the building. Edward had seen the financial burden for his father, however, and was anyway more interested in rebuilding St. Stephen’s chapel in his adjacent palace. Apart from minor works, the rebuilding ceased for the next century.

Edward’s first wife, Eleanor of Castile, died in 1290 in Northamptonshire. The King accompanied her body back to Westminster and wherever they rested for the twelve nights of the journey a stone cross was erected. (The closest remaining original example to London is Waltham Cross in Hertfordshire. That at Charing Cross is a Victorian replica). Edward had tombs created for both Eleanor and his father, which were placed in the chapel close to that of Edward the Confessor.

In 1296 Edward and his army invaded Scotland in retaliation for the Scottish refusal to support his actions against the French who had overrun the English territory of Gascony. They decisively thrashed the Scottish army at the Battle of Dunbar and returned to Westminster with the Stone of Scone as a prize of war. The sandstone slab had for centuries been used at the coronations of Scottish kings. In 1301 Edward ordered the creation of a magnificent wooden chair to house the stone in the abbey for future coronations. The first was that of Edward II in 1308 and there have been 38 English or British monarchs crowned since with the chair. (Only Queen Mary, in the 16th century, has not thus been crowned). The Coronation Chair is said to be the oldest surviving piece of English furniture. The stone was returned to Scotland in 1996 and is currently housed in Edinburgh Castle until it is required for the next coronation.

During that period Edward had moved the royal household to York to be closer to the battles against the Scots. While away from the Palace of Westminster he deposited much of his treasure of plate and jewellery in the crypt below the abbey’s Chapter House, protected by its thirteen-feet thick walls. While the King was away, servants at the palace were rather slack and had taken to drinking with the monks from Westminster.

A merchant by the name of Richard of Pudlicott was held hostage in Flanders and his assets seized as surety against the debts of Edward I. Returning to England with a grudge against the King he arrived at Westminster, apparently to seek redress through the courts. With security less than perfect, in 1303 Pudlicott began to steal some of the abbey’s silverware. He then turned his attention to the royal treasury in the crypt and made off with some items. Initially no alarm was raised until a fisherman on the river netted a silver goblet, a local prostitute was found with a valuable ring taken in lieu of payment, and other items were also found in St. Margaret’s churchyard. Rumours began to reach the King in York and he ordered a check of the inventory. A search of Westminster led to the discovery of items from the treasury under the beds of palace servants and abbey monks. Pudlicott and the entire monastery were immediately imprisoned in the Tower of London, awaiting trial. Edward’s valuables were moved to the Tower where the Crown Jewels remain today. William, a palace servant, and five other suspects were hanged, followed by Pudlicott. The remaining abbey monks were released.

Edward died in Cumbria in 1307 and his body brought back to Westminster where it was buried in a plain tomb in the chapel beside that of his father and Eleanor.