The original Hammersmith Bridge

Hammersmith Bridge was one of the very earliest suspension bridges, and the first in the London area. When it opened in 1827 the original bridge was one of the most elegant on the Thames.

Several years earlier, the engineer Thomas Telford was conducting a survey of a road from London to Holyhead on Anglesey Island, from where ferries could sail to Dublin. The Menai Strait divided the Welsh mainland from Anglesey and had to somehow be crossed. A bridge with piers was out of the question because of the high banks on either side, shifting sands on the seabed, and fast flowing water. It also had to be at a high level to not be an obstruction to shipping. Telford’s revolutionary solution was a bridge held up by iron chains suspended from stone towers on either side. During the time the Menai Bridge was being built, the Union Suspension Bridge was also constructed over the River Tweed, linking Northumberland in England with Berwickshire in Scotland, opening in 1820. The latter was designed by John Rennie, using chains patented by the former naval captain Samuel Brown. At about the same time Rennie was also involved in Vauxhall, Waterloo, Southwark bridges, and the rebuilt London Bridge. The Menai Bridge opened in January 1826.

Clark proposed that the bridge at Hammersmith should use this new idea of suspending it on chains. The idea was well-received because his estimated cost was slightly under £50,000 including land purchase, considerably less than a traditional arched bridge. It also had the advantage of avoiding obstruction to navigation. Before proceeding, Clark verified his plans by submitting them to Telford while he was building the Menai Straits Bridge.

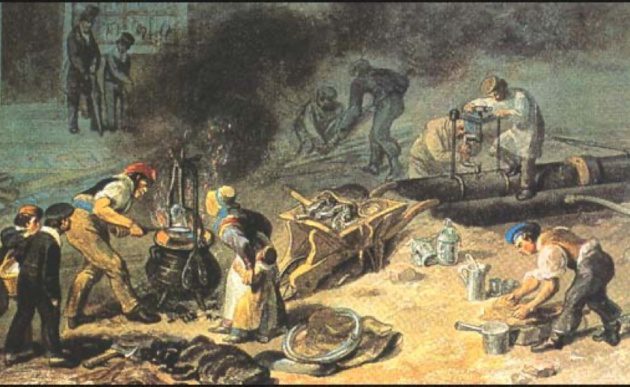

Without local models to follow, and spanning 700 feet between the banks, Hammersmith Bridge was a considerable achievement. The initial design involved tapering towers on either side of the river but they were substituted by monumental Tuscan arches. The towers supported four double rows of chains, and from those hung vertical rods holding the roadway in place. The chains passed through the towers and were then secured to piers on each shore. Each tower was set a short way into the river so the distance between them thus reduced the central span to 422 feet. The roadway was 20 feet wide, but only 14 feet through the arches of the towers. Strangely, the footpaths on either side of the river ended at the towers, forcing pedestrians into the carriageway across the central section. There were two octagonal tollhouses at each end of the bridge, manned by liveried toll-keepers. Tolls were cheaper than at Putney or Kew, with exemptions for soldiers on duty, mail coaches, and those on royal business.

The foundation stone was laid by the Duke of Sussex, bother of George IV, in May 1825. It was officially opened in October 1827 when Lord Ellenborough, a future Governor-General of India, drove over it. It was a great success and provided its investors with a good return.

In 1843 a pier was constructed, connected to the downstream side of the southern tower, for passengers joining steamboats. Stairs led down from the roadway. Being in mid-channel, steamers could operate from there at all states of the tide. It remained in use until 1921.

The bridge became a popular spot to gain a grandstand view of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race, which passed under the bridge from 1846, about half-way along the course of the race. It is said that the bridge began to sway when up to 12,000 people gathered on it, with some climbing up the chains. Those concerns resulted in the bridge being closed on race-days from 1882.

The Metropolitan Board of Works began purchasing London’s toll bridges during the 1860s to make them toll-free. The Metropolis Toll Bridges Act was passed in 1877, allowing the MBW to purchase those that they, or the City of London, did not already own. Hammersmith was purchased for £112,500 in 1880, a rare case of a Thames bridge where the sale made a considerable profit for the owners. On the same day in June of that year the MBW abolished tolls at Hammersmith, Putney and Wandsworth bridges, joining all those downstream that were already toll-free. A ceremony was held to celebrate the ending of tolls, with the Prince and Princess of Wales driving across Hammersmith Bridge in a carriage.

With tolls abolished, traffic increased, and work had to be undertaken to strengthen the bridge. The width of only 14 feet through the arches of the towers, catering for both road and pedestrian traffic, had become a serious bottleneck. Eventually a decision was taken to completely replace the original bridge with a wider crossing, which opened in 1887.

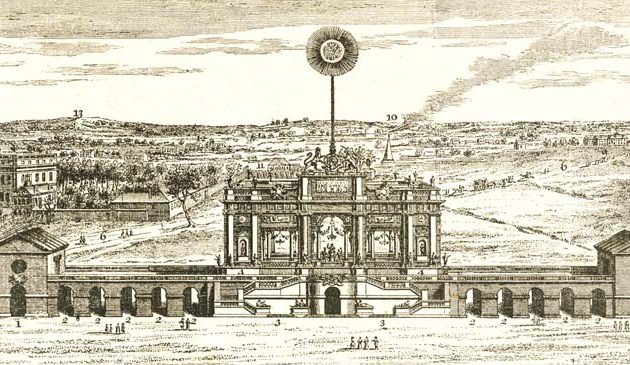

William Tierney Clark continued to design suspension bridges using the same basic design as Hammersmith. It was followed by those at Marlow and Shoreham-by-Sea. The Hungarian politician Count Széchenyi had a strong interest in the industrialisation of Britain and came to view Hammersmith Bridge. That led to a commission for Clark to create his most famous work, the Széchenyi Chain Bridge over the River Danube. It was the first to link the twin towns of Buda and Pest and remains a symbol of the city. The Count visited Clark at Hammersmith several times to discuss the project. At the foundation laying ceremony in August 1842 Clark was presented with a gold and diamond-studded snuff box from Emperor Ferdinand of Austria. The bridge at Budapest, which is still in use, provides a good idea of what Clark’s Hammersmith Bridge looked like. He also received a medal from the Tsar of Russia for the design of an unbuilt bridge at St. Petersburg. When he died in 1852 Clark was buried in St. Paul’s church at Hammersmith, where his memorial includes a picture of his Hammersmith Bridge. Hungary continues to present an annual engineering award in his name.

Sources include: Peter Matthews ‘London’s Bridges’; John Pudney ‘Crossing London’s River’; John Summerson ‘Georgian London’; Brian Cookson, London Historians newsletter, August 2014; Daniel Defoe ‘A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain’ Vol. II (1725); Sir Joseph Broodbank ‘History of the Port of London’ (1921)

< Back to Bridges and Tunnels