The Thames Tunnel

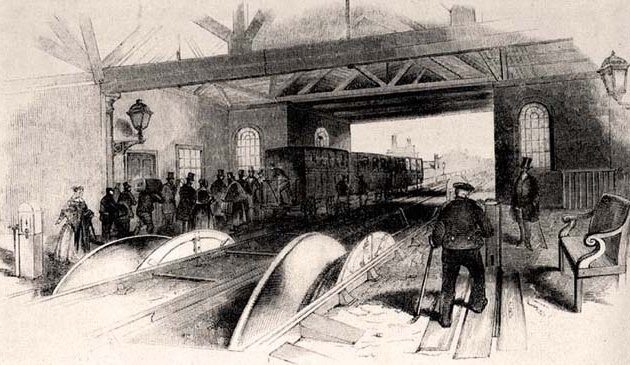

The opening ceremony of the Thames Tunnel on 25th March 1843. The procession walked through the tunnel from Rotherhithe to Wapping on one of the carriageways and then back to Rotherhithe on the other carriageway. Marc Brunel (on left holding his hat) acknowledges the cheering of well-wishers.

In large part, Vazie and Trevithick’s failure was because the necessary tunneling equipment had not yet been invented. It was a Frenchman who had moved to England who overcame that challenge. Marc Isambard Brunel fled France to the recently formed United States during the French Revolution. There he became an America citizen and was involved in a scheme to link the Hudson river by canal to Lake Champlain. Three years after his arrival in the country he was appointed Chief Engineer to New York City. During that period he designed commercial buildings, docks, an arsenal and a cannon factory.

Brunel then heard of the British navy’s difficulties in producing pulley blocks for its ships. He travelled to England and presented an idea to Samuel Bentham (younger brother of the philosopher Jeremy Bentham), Inspector General of Naval Works, for a machine to dramatically speed up their production. Brunel’s machine was subsequently used at the naval yard at Portsmouth and he was greatly compensated. By then he had married Sophia Kingdom, an English woman he had first met before leaving France. They had three children, the youngest of which was Isambard Kingdom. Brunel continued to work on various projects to improve saw-mills, including some for the naval shipyards. In 1814 he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society. Some of his schemes led him into debt, however, and in 1821 he spent time in the debtors’ prison at Southwark. With no likelihood of release, he wrote to the Russian Tsar regarding moving to that country to create a tunnel under the River Neva in north-western Russia. On hearing of this, the Duke of Wellington persuaded the government to pay Brunel’s debts so he could be released and stay in Britain.

While undertaking some work at Chatham naval dockyard Brunel witnessed a ship-worm digging into wood removed from a ship. Using a magnifying glass he noted how the worm used two razor-sharp shells to cut into the wood, grind the wood into a flour for its food, then excrete to form a lining for the tunnel it was digging. That gave Brunel the idea to create a machine to reproduce the worm’s actions. It involved an iron cylinder propelled forward by jacks. Inside the cylinder miners could bore forwards and behind them others could line the tunnel with bricks. Brunel took out a patent for his initial design in 1818, which was subsequently modified over the years until it became the ‘Great Shield’.

In 1823 Brunel began canvassing for a tunnel under the river, sending pamphlets to, and meeting with, bankers, businessmen, and directors of canal companies. Early the following year he held a public meeting and within three days had raised £180,000. He visited the Duke of Wellington to explain his idea and the statesman duly became a subscriber. The Thames Tunnel Company was formed in 1824, with four thousand £50 shares issued, and Brunel as the chief engineer.

An Act of Parliament was duly obtained for the making of a toll tunnel between the parishes of St. John, Wapping and St. Mary, Rotherhithe, which was three quarters of a mile upstream from Vazie’s attempt. The river is relatively narrow at that point so a tunnel could be shorter. Napoleon had been defeated some years earlier so there was by then no military need to consider. Watermen at that time carried no less than 3,700 passengers across the river daily in the neighborhood. The tunnel was to be designed for wagons, carriages, pedestrians and animals. William Smith was appointed chairman of the company but he and Brunel had major disagreements regarding how the tunnel should be dug.

A headquarters was established at Cow Court, Rotherhithe (now the site of the Brunel Museum). Workshops were constructed for carpenters and blacksmiths, as well as storerooms and offices for draftsmen and accountants. Brunel moved to the area with his family.

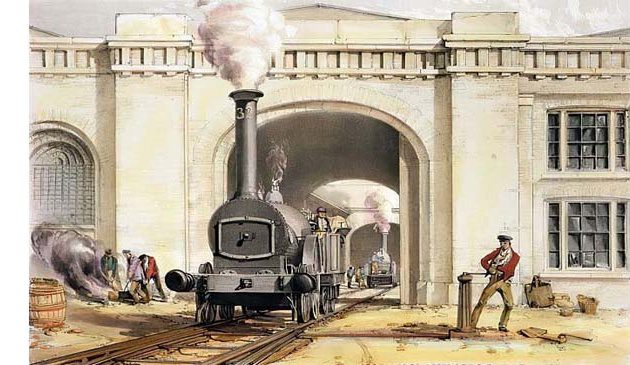

The company of Joliffe & Banks were contracted to carry out test borings. They were one of the leading engineering companies of that time whose work included the West India Docks, Waterloo Bridge, Southwark Bridge and Rennie’s London Bridge. A round tower was built in the centre of Cow Court consisting of a 55 feet wide metal ring with brickwork above it. That was allowed to sink into the soft ground under its own weight and the earth inside the tower dug out to form a shaft with the aid of a steam engine.

The start of work in March 1825 was a public event, with carriages bringing spectators, including Prime Minister the Duke of Wellington and Home Secretary Robert Peel, and the bells of the nearby St. Mary’s church rang throughout the day. Dignitaries climbed into the shaft: the men descended by ladder and ladies lowered on a chair. While a band played, the first two bricks were laid by Brunel and his son. Isambard had joined his father to work on the project the previous year.

After four months of construction one of the workers fell down the shaft and died. All went well for the remainder of 1825. When the shaft reached a depth of 63 feet work began on the tunnel, with the tunneling shield manufactured by the machine-tool specialist Henry Maudslay, who had earlier built Brunel’s pulley block machine, at his workshop at Lambeth. The shield was assembled underground and large enough that it could accommodate 36 miners working at the same time. Brunel planned for the tunnel to pass just fourteen feet below the river bed at its lowest point, which subsequently become a major problem during the course of construction.

The tunnel was mostly dug through a seam of strong blue clay but above and below that are softer clay, water-soaked gravel, and quicksand. However, the blue clay seam was not continuous. In 1826 workers hit loose gravel and quicksand and pumps had to be employed. In May carburetted gas began to cause sickness and heat from the shields caused the gas to ignite, burning the hair of workmen. That month two men died from the effects and others fell sick.

Work continued, however, and the Brunels and directors maintained interest in the project by inviting guests to inspect the work under the river, including holding concerts in the tunnel. In May 1827, when 544 feet in length had been achieved, Isambard and the workers just managed to escape when the river burst through, bringing in a thousand tons of soil and filling the tunnel with water in fifteen minutes. To find the cause he descended from above using a diving bell borrowed from the West India Dock Company and rowed a boat into the workings. A hole in the riverbed 38 feet deep was found, which was plugged with 3,000 bags of clay and gravel. Directors went into the water-filled tunnel to inspect but the boat capsized and a worker drowned.

The water was pumped out and work continued in September, with men working in shifts night and day. In November the tunnel was decorated with crimson drape, lit by candelabra, and a banquet held for 40 distinguished guests to restore confidence in the venture, as well as 120 workmen. The band of the Coldstream Guards provided the music. A toast was made to celebrate the naval victory over the Ottaman Turks in the Battle of Navarino by the fleet commanded by Admiral Codrington, one of Marc Brunel’s supporters. Marc Brunel suffered from ill-heath during the course of construction and the celebration was hosted by the 21-year old Isambard.

It was not long, however, before disaster struck again. In January 1828, at almost 600 feet in length, the tunnel was flooded. For a second time Isambard narrowly escaped, although with injuries requiring him to be laid up for months. This time six workers lost their lives, three of whom were by his side when the water came in. The hole in the riverbed was patched with 4,000 tons of earth. The catastrophe caused a loss of confidence by investors, however, and work halted for seven years due to the Brunels’ inability to raise further funds. In the meantime, the workings were sealed off by a large mirror and the completed part of the tunnel became an attraction, with visitors paying for the novelty of walking under the river. Marc Brunel continued to clash with William Smith and resigned his position of chief engineer. Smith was deposed as chairman in 1832. In the meantime, the engineer George Stephenson had created the Edge Hill railway tunnel below Liverpool, which was completed in 1829, the world’s first under a city.