Dissolution of the London monasteries

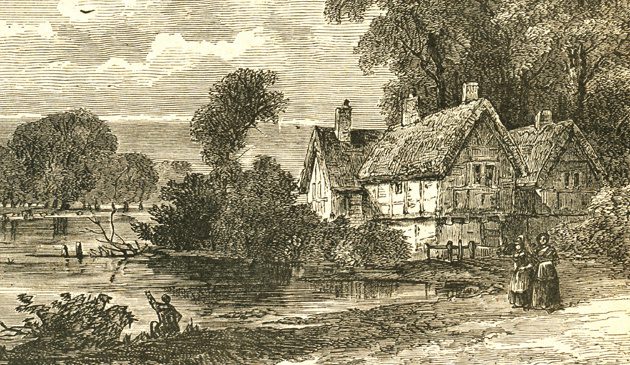

The ruins of the Convent of St. Clare’s at Aldgate, just outside the city wall, in a print published in 1797, more than 250 years after its dissolution. It had been founded in 1293 by the brother of King Edward I and his wife, the Queen of Navarre, and dedicated to St. Clare who had died fifty years earlier at Assisi. The nuns were known as Minoresses and their memory is perpetuated in the street name Minories, which today runs on the east side of the former convent. Part of its grounds later became a farm known as Goodman’s Fields.

Larger monasteries began to be closed from 1538, beginning with Bermondsey Abbey at the start of the year, followed by Blackfriars, Grey Friars in Newgate Street, Whitefriars at Fleet Street, St. Helen’s priory at Bishopsgate (the dormitory of which was acquired by the Leathersellers’ Company), St. Mary’s Priory at Merton, Austin Friars, St. Martin’s le Grand and Stratford Langthorne Abbey.

More closures took place the following year: the great St. Bartholomew’s Priory at Smithfield (much of it later coming into the ownership of Sir Richard Rich); Holywell Priory in Shoreditch; Crutched Friars, inside the city walls near Aldgate; St. Mary Graces outside the City wall near the Tower (demolished by Sir Arthur Darcie, the site later becoming in turn a naval storehouse, the naval office associated with Samuel Pepys, and the Royal Mint); Southwark Priory; St. Giles’s hospital; St. Mary’s nunnery at Clerkenwell; Syon Abbey; and Sheen Priory. Barking Abbey, in which William the Conqueror had lived almost 500 years earlier during the construction of the Tower, was another victim. In 1541 all but its curfew tower was demolished and its stones used for repairs at Greenwich Palace.

The Abbey of St. Clare, outside the City wall near Aldgate was surrendered in the same year. After its dissolution the abbey’s chapel was given over to the local people as their church and survived until the 19th century. Its land became a farm, later known as Goodman’s Fields. St. Clare’s had previously been a ‘papal peculiar’, meaning that it answered to the Pope instead of the Bishop of London, and at its dissolution it became a ‘royal peculiar’. Edward VI and Queen Mary failed to actually bring it under control, however, and the precinct became an ‘Alsatia’ outside of the City wall. Clandestine marriages were performed in the church and criminals were able to freely deposit stolen goods. The parishioners appointed their own ministers, who claimed freedom from jurisdiction of bishops or archbishops, as well as magistrates, and they licensed publicans. They paid no public taxes and claimed exemption from arrest while outside the precinct. Thirty-two thousand marriages were performed during the second half of the 17th century. The last freedoms of the Minories were finally abolished in 1894.

St. Mary’s Spital was surrendered to the Crown in January 1539, coming into the ownership of various royal courtiers. At that time there were 180 beds in its hospital. The Prior and canons had already acknowledged Henry’s supremacy several years earlier and thus in 1539 they were rewarded with pensions. For the following hundred years its fabric underwent changes, with parts left in ruins for a lengthy period. By 1560 much of the priory had gone. The great church tower had been demolished and the interior of the church converted to gardens and courts. The buildings that surrounded the church were converted into houses and tenements. The tradition of the annual sermon from Spital Cross, one of London’s great annual events during the Middle Ages, continued into the 17th century until being relocated to St. Bride’s Fleet Street in the 1680s. The former land of the priory became the liberties of Norton Folgate and the Old Artillery Ground.

The Order of the Knights of St. John, which could trace its ancestry back to the time of the Crusades, was dissolved in 1540, along with Kilburn Priory, and its premises of St. John’s Gate at Clerkenwell acquired by the King to be used for storage of his hunting tents. The beautiful tower was later blown up by the Earl of Somerset, Protector to Edward VI, to provide materials for his Somerset House.

Westminster – St. Peter’s Abbey – was dissolved gradually over a number of years. A new, compliant abbot was appointed by Thomas Cromwell in 1533. Three years later the monastery’s manors of Ebury, Hyde, Toddington, Neyte and Covent Garden were given to the King. Some of its lands were transferred to St. Paul’s Cathedral, hence the expression ‘robbing Peter to pay Paul’. In 1540 the abbot and the remaining twenty-four monks agreed to surrender the abbey and the authorities ransacked the building, taking everything of value.

St. Paul’s Cathedral had lacked a strong, leadership for a generation. In 1534 its canons and priests acknowledged Henry as head of the Church in England. From 1535 the cathedral functioned under the auspices of the Royal Supremacy, in the person of Thomas Cromwell, the King’s vice-gerent, a proponent of religious reform. That October Cromwell granted the cathedral a licence to continue spiritual jurisdiction.

St. Katharine’s, outside the City beyond the Tower, had for centuries enjoyed the patronage of the Queen Consort or Queen Dowager. Despite Henry’s annulment of his marriage Catherine continued as the priory’s patron. Henry’s and his second wife, Anne Boleyn, visited on several occasions. Anne never became its patron during the three years of their marriage, although it is said that it was her who dissuaded Henry from his intention to have it dissolved. It was never dissolved and during the following decades became a Protestant establishment. The foundation continues into modern times and is currently based in Stepney.

Various groups benefited from the seizures. Firstly, there was Henry himself who was able to acquire certain properties that could be used to build new palaces, as well as parks to be used as hunting grounds. He also gained directly or indirectly from land and property that was auctioned, with proceeds going to the royal purse or the Exchequer. Secondly, there were former tenants of the religious houses who were sold or granted use of the properties. Urban property was generally released on to the market or given away. A number of royal courtiers and officials who were in favour at the time were granted or were able to acquire properties, particularly those at the Court of Augmentations, which was responsible for the transfers. Sir Thomas Cawarden, Master of the Rolls, gained Blackfriars monastery; and the Lord Treasurer, Sir William Paulet acquired Austin Friars monastery. Bermondsey Abbey came into the ownership of Sir Thomas Pope, Treasurer of the Court of Augmentations. (Pope also acquired the Benedictine Durham College at Oxford, which he re-founded as Trinity College, at which students were required to pray for the soul of their founder). Thomas Audley, one of the King’s most loyal ministers, acquired the Augustinian priory of Holy Trinity at Aldgate.