London’s earliest long-distance railway

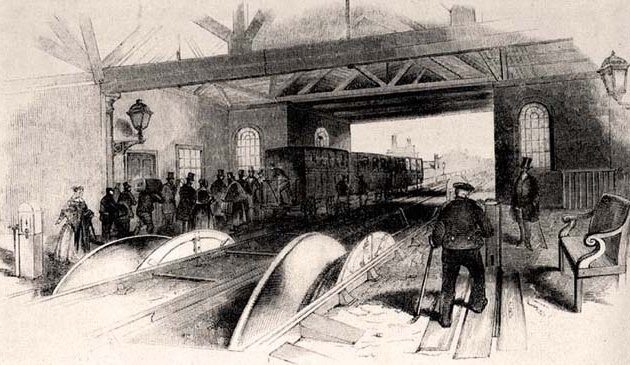

The entrance to the engine shed of the London & Birmingham Railway at Camden in 1838. This coloured lithograph was one of 50 made by the London artist John Cooke Bourne. He is best known for his pictures of the construction of the London & Birmingham and Great Western Railways, which were published in four volumes in 1838 and 1839. His interest in the railways was sparked when construction of the L&BR was taking place near his home.

The Euston extension was completed in July 1837 and the directors took invited guests on a 25-mile excursion from London to Boxmoor in Hertfordshire, a journey of just over an hour, where a lunch was given. It was quite an eventful return journey. The locomotive derailed and also had to stop several times due to a miscalculation regarding the required amount of water in its reservoir. Worse was to come, as reported by the Bucks Herald newspaper:

Just as this train had reached the terminus at the back of Euston square, the engine having been disengaged, but the impetus still continuing at a considerable velocity, the men whose duty it was to check the motion by working what are technically called the ‘breaks,’ [sic] not being sufficiently expert, or miscalculating their power, the carriages came with frightful force against the barrier wall at the extremity of the line, dashing it to atoms, and causing a rebound which frightened all and damaged not a few. The concussion was so great that those sitting opposite in the different carriages being thrown against each other with great violence, we are sorry to say some instances of serious injury occurred. Among others Lord Hatherton received a severe bruise on the cheek; Mr. N. Calvert, formerly M.P. for Hertfordshire, violent contusions on the face; two gentlemen and a lady had their noses broken; others lost their front teeth, and several sprained their wrists and arms.

It was hoped that the L&BR would be complete at the same time as the Grand Junction from Liverpool but there was trouble in creating a tunnel in Northamptonshire, so the L&BR was to open a year after the GJR.

By June 1838 the entire route was still incomplete. Anticipating many visitors to London for the coronation of Queen Victoria the company started running trains on a section south from Birmingham to Rugby, bringing people from as far as the North-West. Stagecoaches then carried passengers over the uncompleted section between Rugby and Bletchley.

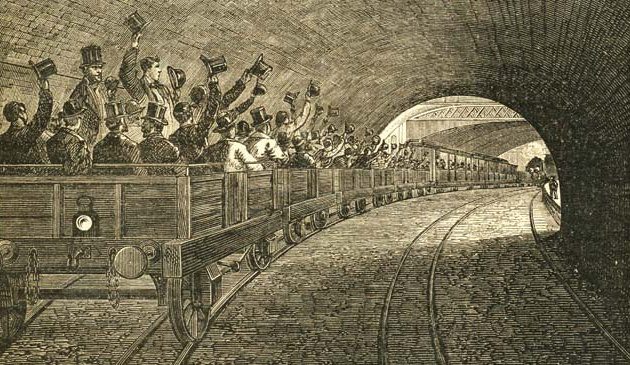

Trains were finally able to travel the complete distance of 112½ miles from London to Birmingham in September 1838. With a maximum speed of 22½ miles per hour the journey took 5½ hours, which compared favourably with an uncomfortable ride of a full day by stagecoach. At the beginning there were three trains each way daily, with up to 40 carriages, rising to nine return services each day within that year.

Within four years there were ninety locomotives working on the railway. The company had them built by various workshops but their management was initially contracted out before being brought in-house. There were three classes of carriage: first class, enclosed second class, and third class that was open to the weather. Wealthier passengers could load their carriages onto flat wagons and remain in them for the journey, with the horses carried in a separate wagon.

There were initially only 16 stations along the line, including Coventry and Rugby but not all services stopped at half of them. The first out of London was at Harrow, over 11 miles away from the capital and with only occasional trains stopping there. It consisted of a modest single-storey building and without a platform.

Other railway companies were formed and from 1839 new, independent lines joined the London & Birmingham. Thus, towns across the Midlands could be reached. Time had not yet been standardised, with each town having its own time. L&BR timetables included a conversion showing the difference between London time and that of each town along the route.

The Royal Mail soon realised the opportunity provided by railways, and special mail coaches were introduced after just a few months. In 1838 the L&BR introduced ‘travelling Post Office’ wagons and the first apparatus allowing mailbags to be dropped or collected from a fast-moving train.

For its first 15 years of existence, until the opening of the Great Northern Railway’s King’s Cross station, Euston remained London’s only rail gateway to the Midlands and North of England. Passenger numbers exceeded the projections of the company. Freight traffic was slow to transfer from canals but coal, in particular, eventually became one of the most common commodities to be transported.

The Great Western Railway gradually opened from London to Bristol in sections between 1838 and 1841. Several years later they planned a new line from Oxford to Birmingham and that, in part, prompted the amalgamation of other railway companies. In 1846 the L&BR merged with the Grand Junction Railway and Manchester & Birmingham Railway to form the London & North Western Railway. The new conglomeration initially had a network of approximately 350 miles.

Sources include: Ian Petticrew, Wendy Austin ‘The Train Now Departing’ https://tringlocalhistory.org.uk/Railway/index.htm; G.A. Sekon ‘Locomotion in Victorian London’; Christian Wolmar ‘Cathedrals of Steam’; Christian Wolmar ‘The Subterranean Railway’; Professor Joe Cain ‘ Euston Grove – A History of a London Street’ https://profjoecain.net/euston-grove-history-london-street-nw1/