The original Putney Bridge

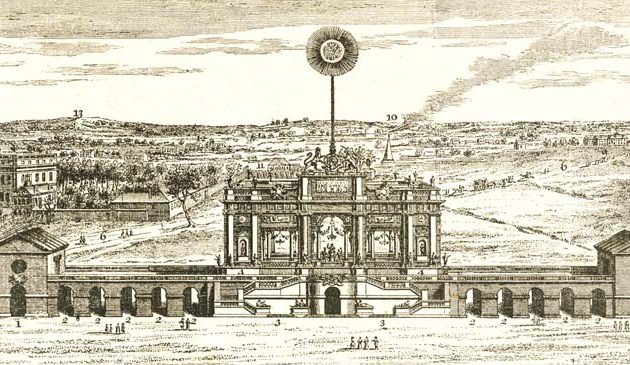

Here we see the old, wooden Fulham Bridge, looking towards Putney. The toll-house in the foreground also acted as a meeting room for the proprietors. Each of the piers was v-shaped, facing into the river, and providing shelter for pedestrians from oncoming carriages.

One thousand seven hundred years after the Romans constructed the original London Bridge it remained the only dry crossing over the Thames between the city and the old medieval structure upriver at Kingston. Finally, in the mid-18th century a new bridge was created to carry traffic between the city and the South-West of England.

Despite the inconvenience to travellers, the City of London, which represented members of the Company of Watermen (who operated water-taxis and ferries), as well as profiting directly from tolls charged at London Bridge, successfully fought against any plans for new crossings over the Thames. A proposal in the House of Commons in 1671 for a bridge at Fulham was successfully defeated when the extraordinary argument was put forward that it would extend the boundary of London beyond the city wall and thus “England itself shall be as nothing”.

Fulham on the north bank of the river is an old settlement, existing as a manor from at least early Saxon times. In the 9th century it was occupied for a time by Vikings. The ancient Fulham Road joins the one from Hammersmith to become Fulham High Street that then led down to the river. Immediately west of the High Street, on the riverside, stands Fulham Palace, for centuries the manor house and country home of the Bishops of London. Almost facing each other on opposite banks are the old Fulham parish church of All Saints, noted in the early 19th century for its peel of bells, and St. Mary the Virgin, or Putney Church. Putney was part of the Manor of Wimbledon and in Norman times was a place of little consequence other than a fishery, which became noted for its salmon, smelt, and occasional sturgeon or porpoise. In October 1647 Putney Church was the venue for the debate by the Republican New Model Army, chaired by Oliver Cromwell, on the future constitution of England. Putney’s main street led uphill from the river to Putney Heath and Wimbledon. During the 19th century, from 1836, the quiet village came alive each year at the time of the Oxford and Cambridge boat race. Events tended to centre around the riverside Star and Garter pub, and in the mid-19th century the London Rowing Club established its own club-house there.

There was already a ferry from Fulham to Putney by Norman times. It was occasionally a dangerous crossing over the tidal river, such as the time one night in 1633 that a boat capsized when it was transporting some staff of Archbishop Laud. Robert Walpole is said to have once been kept waiting on his way from Richmond to Westminster for an important parliamentary debate. When a new proposal was put forward for a privately-funded toll bridge in 1725, during the reign of George II, it therefore gained the minister’s backing and an Act was passed the following year. A condition was that the proprietors paid compensation to the Bishop, as well as the Duchess of Marlborough (Lord of the Manor of Wimbledon on the south bank), for their loss of ferry income. Furthermore, they and their staff had the privilege of crossing the bridge for free, which led to abuse by those claiming such a right. The sum of £62 was also to be divided annually between the widows and children of the watermen of Fulham and Putney. The bridge company sold thirty shares in the venture at £1,000 each. They then purchased the ferry for the large amount of £8,000.

Five designs were considered for the new Fulham Bridge as it was then known. Although accounts vary, it would appear that the successful design was by Sir Joseph Ackworth (who also designed bridges at Windsor, Kingston, Chertsey, Staines and Dachet) and William Cheseldon (a surgeon at either or both St. Thomas’s and Chelsea hospitals). It was constructed by the royal carpenter, Thomas Phillips, and the official opening was in November 1729.

The bridge was built entirely of wood, 786 feet long and 24 feet wide. It had 26 spans of various widths, supported on piers that were v-shaped, providing triangular platforms at road level in which pedestrians could take shelter from passing carriages and wagons. The cost was slightly under £9,500. It was built in line with Fulham High Street but as that was not directly in line with Putney High Street a curve was created in the bridge on the Putney side in front of the church so it did not have to cross the river at an angle. A large toll gate-house stood across the passage-way on the Fulham side, which also acted as the bridge company’s office, with a smaller red-brick toll-house on the Putney side. Two toll-collectors were stationed at each end, dressed in dark blue gowns and hats, carrying staves with a metal head. If anyone passed on either side without paying their fee a bell was rung to warn the toll-house on the far side. It was originally illuminated by oil lamps, which were replaced by gas lamps in 1845.

After the bridge opened there was an increase in traffic passing from one bank to the other, particularly from stage coaches, successfully bringing in tolls for the company. However much of the income was required to maintain the wooden structure, which was regularly hit by barges passing underneath, as well as occasional damage from ice floating downstream in winter.

A notable event during the life of the old bridge was the attempted suicide in 1795 of Mary Wollstonecraft, the feminist writer. She was saved by two watermen but died in 1797 shortly after giving birth to her daughter, Mary, who went on to marry Percy Bysshe Shelley and to write the novel Frankenstein.

Fulham Bridge was not handsome according to contemporary accounts. In The Book of the Thames, published in 1859, the author wrote:

We resume our voyage…we come in sight of the ugly structure – ungainly piles of decaying wood – which, crossing the Thames, unites the villages of Putney and Fulham.

The bridge was taken over by the Metropolitan Board of Works in 1879 and became toll-free the following year.

The old wooden crossing was not strong enough to withstand increasing road traffic and the spans too narrow for river traffic so it was replaced by a new, stone structure. The new crossing, to be known as Putney Bridge, was slightly upstream of the old and in line with Putney High Street, allowing it to be constructed while the older was still in place. The more traditional design was by Joseph Bazalgette, engineer of the MWB, with his son Edward assisting on the project. It was 700 feet long and 44 feet wide, with five arches and a central span of 150 feet. Pipes of the Chelsea Waterworks Company were laid under its surface. The new bridge was opened by the Prince and Princess of Wales in May 1886. Overall it is quite a plain structure but is pleasantly decorated with ornate lamps.

From 1909 trams ran over the bridge and it was thereafter too congested. Twenty years later the London County Council decided to widen it by 30 feet to its current width, with work completed in 1933. To achieve the widening the churches on both banks each lost part of their graveyards.

Sources include: Peter Matthews ‘London’s Bridges’; Edward Walford ‘Old & New London’; S.C. Hall ‘The Book of the Thames’; Ian Pay etc. ‘London’s Bridges – Crossing the Royal River’; John Richardson ‘Annals of London’.

< Back to Bridges and Tunnels