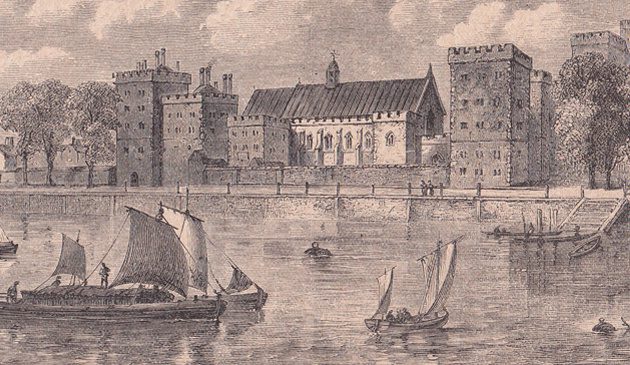

St. Paul’s Cathedral in the early Stuart period

The old St. Paul’s from the west showing the Italianate portico designed by Inigo Jones. It was added to the west front as part of the extensive refurbishment of the building in the 1630s. The print was made as part of a series by Wenceslaus Hollar as a commission to illustrate William Dugdale’s History of St. Paul’s, published in 1658.

The mighty St. Paul’s Cathedral stood tall over the City of London. Yet at the start of the 17th century its fabric was in poor condition so major work began that significantly changed its appearance. Before the transformation was complete it was interrupted by the maelstrom of national religious and political events.

In the early 17th century British Protestants were increasingly divided between those who followed the Anglican Church and Dissenters of various denominations. At St. Paul’s Cathedral there had been since the late 16th century a tendency towards ‘ceremonialism’, which supporters believed to be “reverence” and critics to be “idolatrous” and “popish”. During the reign of King James the move to ceremonialism was confirmed with the appointment of John Overall, one of its supporters and an anti-Calvinist, as dean.

In January 1606 eight of the Gunpowder Plot conspirators, including Guy Fawkes, were hanged, drawn and quartered in the churchyard at St. Paul’s. The event was popular with London’s anti-Catholic majority and stands were erected for those willing to pay for a better view. In May of that year the same fate befell England’s leading Jesuit priest, Father Henry Garnet. The assembled crowd were more sympathetic in his case and pulled at his legs while he was hanging so that he died quickly, ensuring that he would not be drawn and quartered while still alive.

The old medieval cathedral was in a poor state by the 17th century. The building had long been used as a place to meet and shelter and had degenerated into as much of a market as a place of worship, complete with traders, pick-pockets and others. In 1561 its spire had been destroyed by a lightning strike and the central tower patched up with a flat roof. A structural survey was undertaken in 1608 but no action taken. King James visited in 1620 to make his own inspection of “the Ruines” and a fund was created to carry out work. Some Portland stone was acquired but otherwise nothing further was undertaken. Instead, the Duke of Buckingham, a favourite of both James and Charles I, ‘borrowed’ the stone to create a watergate at his York House.

In 1628 the more determined William Laud was appointed Bishop of London. King Charles attended a sermon at Paul’s Cross in the cathedral churchyard in 1630 and was persuaded to form a commission to consider the problem of the deteriorating fabric of the building. It concluded that St. Paul’s was the “most eminent Church of our whole Dominions” and that action should be taken to preserve it. A new fund was created, to be managed by the City of London, and Laud was tenacious in persuading the King, wealthy individuals, and local parishioners from far and wide to contribute. That money gradually arrived from dioceses and parishes across the whole country, from many who had probably never seen the building, indicates that St. Paul’s was widely seen as an institution of national significance and not simply the mother church of London. In order to restore some of the cathedral’s prestige and not jeopardise contributions, efforts were made to limit the misuses of the building that had been occurring for many years. More than a £100,000, a considerable sum in those days, was raised in just five years.

The artist and architect Inigo Jones was appointed as the cathedral’s surveyor in February 1633 with a mission to improve the building. Jones was an early devotee of neo-classical architecture, who had designed the Banqueting House at Whitehall Palace and the Queen’s House at Greenwich. His changes were radically different to the Romanesque style of the medieval building.

In April 1634 King Charles informed Archbishop Laud that he wished for a new west front to the cathedral, for which he would contribute £500 for the following 10 years. Jones designed a grand new front in the classical style, faced in Portland stone with black marble steps. The vast portico of this new entrance, with eight giant fluted Corinthian columns of 45 feet in height, was said to be the tallest north of the Alps. The exterior walls of the nave and transepts were remodelled in classical style with pilasters and bulls-eye windows, replacing the Norman buttresses.

In the first four years of restoration Edmund Kinsman and a team of 70 masons, carvers and masons worked on the south side of the choir. From April 1634 they were joined by two further teams, working at the east end and the north side of the choir. From 1635 a team spent up to four years of internal painting.

When St. Paul’s had been expanded in the 12th century it overwhelmed part of the adjoining parish of St. Gregory, requiring the local parish church to be incorporated onto the side of the cathedral building. Jones’s plan was to sweep away the ancient St. Gregory’s. When demolition work started, however, the parishioners protested so vociferously that plans had to be changed and he rebuilt the small church.

Construction of Jones’s designs began in 1633 and continued for several years but ceased in September 1642 before it could be completed. The central tower, which was propped up with timbers, was due to be demolished and replaced but work halted, with scaffolding still in place, as additional funds dried up, workmen went unpaid, and national events interrupted the work.