The Regent’s Canal

A horse-drawn narrowboat owned by the Pickford company passes under Macclesfield Bridge, named after the Earl of Macclesfield, then Chairman of the Regent’s Canal Company. The bridge carries the northern entrance to Regent’s Park over the waterway. In 1874 it was demolished by an explosion and rebuilt, gaining its common name of ‘Blow-Up Bridge’.

After debate in Parliament, an Act was passed in the summer of 1812, incorporating a wide range of details such as where the water could and could not be taken to feed the canal, how much could be charged for freight carried, and a fine for anyone caught swimming in the water. The process of acquiring the necessary land went ahead, held up for a time by lengthy negotiations with the barrister Willam Agar, who had purchased the Manor of Pancras in 1810 and held out to gain the maximum remuneration. In the end, Parliament had to intervene in the matter and, angered by what they felt was Agar’s greed, awarded him less than the Regent’s Canal Company were offering.

Neither Nash nor Homer had any experience of cutting a canal and the necessary tunnels, so a search for an engineer began by means of an advertisement. The advice of John Rennie, successful architect of docks, bridges and canals, was sought but he declined to be involved, perhaps because of his recent problems with a road tunnel at Highgate. When no-one came forward the task was given to Nash’s assistant, James Morgan.

Work began in October 1812. The section through Regent’s Park was the first to be completed in November 1813. The entire lock-free stretch from Paddington, through the park to Hampstead Road (Camden Lock), including the Maida Vale Tunnel, was completed and opened on the birthday of the Prince Regent in August 1816.

In 1815 it was discovered that Homer had been embezzling company funds and he fled the country. He was later apprehended and sentenced to transportation. The problem caused a shortfall in the company’s funds resulting in a halt to the work, and an additional £300,000 had to be raised. After the ending of the Napoleonic War there was a surplus of workers and resulting unemployment. The government introduced the Poor Employment Act in 1817, a Regency-period job creation scheme, and the company was able to take advantage of labour, paid from government funds.

An Act of Parliament of 1819 authorised three basins to be dug adjoining the canal for the unloading of goods: Horsfall Basin at Battle Bridge (what later became Kings Cross); at City Road (which spanned either side of the City Road) and the nearby Wenlock Basin in Islington. Being close to the City of London, City Road Basin in particular became very busy after the canal opened and eclipsed Paddington in the amount of goods trans-shipped.

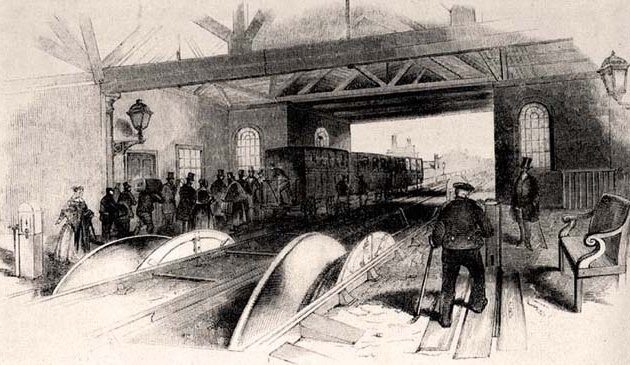

One of the biggest challenges in the building of the waterway was in passing Islington Hill. It was decided to dig cuttings on either side of the hill and then a tunnel, from under the White Conduit House on the eastern side to close to the Rosemarie Branch inn on the western side. The underground section was (and remains) 1,000 yards long, passing under the new suburb of Pentonville, Islington, and the New River. It was completed in 1818.

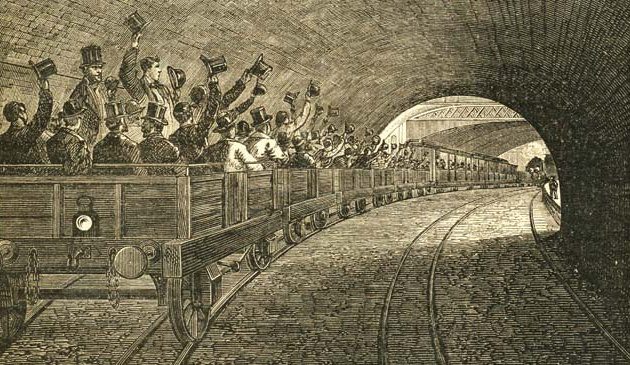

The entire canal was opened in August 1820 in a ceremony in which John Nash, James Morgan, and the company directors travelled from Battlebridge to the new Regent’s Canal Dock at Limehouse by ceremonial barge to the sound of brass bands, passing waving crowds.

The completed waterway is eight and a half miles in length between Paddington to Limehouse, dropping 86 feet during its course. To travel from one end to the other barges must pass through 12 locks between Hampstead Road at Camden and Limehouse (with the stretch from Camden to Paddington on one level and thus lock-free). The locks, tunnels and bridges were all built to the same width as the Grand Junction Canal, allowing for wide barges (or two narrow barges side-by-side) in the locks. At the time of its completion it passed under 37 bridges. Regent’s Canal Dock at Limehouse, just to the west of St. Anne’s church, was built with a lock from the Thames allowing ships to enter during high tides. The total cost of creating the canal was over £770,000, twice the original estimate.

Canals are artificial waterways and therefore need to be somehow fed with water at the same rate as locks are filled and emptied. The Regent’s Canal travels downhill from Paddington to Limehouse. Each of the locks was doubled up, two locks beside each other, so that when a boat passes through one the water can flow into the other and thus some water was saved.

The Acts of Parliament that approved the creation of the Regent’s Canal stipulated where it could not take its water from, which, crucially, included the adjoining Grand Junction Canal. To prevent water passing from one waterway to the other a lock was built at the entrance to the Regent’s Canal, not to take boats from one level to another (as is normally the case with locks) but simply to prevent any flow of water out of the Grand Junction Canal. The Regent’s Canal Company therefore purchased 120 acres of Finchley Common in the hope that enough water could be drained off and channeled from there but it proved woefully inadequate. Various other ideas were considered and tried but the company finally created the Brent Reservoir to the north west of London by damming the River Brent and channeling water from there.