The development of Mayfair

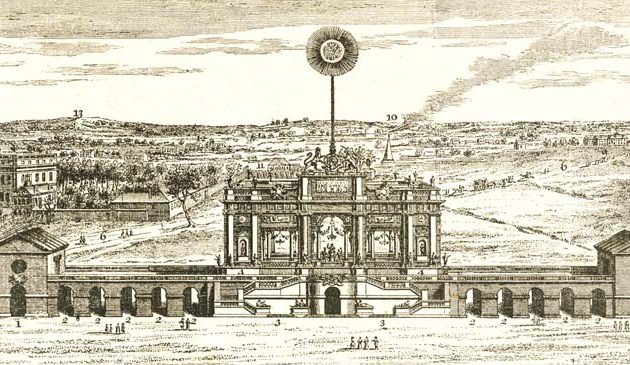

Hanover Square in 1750, looking south towards George Street and St. George’s church.

In 1677 the wealthy Sir Thomas Grosvenor of Cheshire married the 12-year old Mary Davis, daughter of the City scrivener Alexander Davies who had died in the Great Plague of 1665. The Davies family owned 500 acres of land, consisting of 100 acres of meadow to the south east of Tyburn (the modern Marble Arch) and a further 400 acres at what would later become Belgravia and Pimlico, inherited from a rich uncle Hugh Audley. The River Tyburn ran through the estate making the land marshy and of low value for anything other than grazing animals until London spread westwards and ever-nearer. In 1686 James II granted permission for a fair to be held in the first two weeks of each May to the south of the estate (at what is now Shepherd Market) and this event, and subsequently the area, became known as ‘Mayfair’.

Sir Thomas died in 1700 and his son, Sir Richard Grosvenor, inherited the land. In 1711 he obtained an Act of Parliament allowing him to lay out streets and grant leases for housing. It took a further ten years for work to commence, by which time the Hanover Square development to the east and the area around Shepherd Market to the south down to Piccadilly had been established. It was then possible to link the new streets of the Grosvenor estate to those that had already been laid out.

The central feature of the Grosvenor Estate was (and remains) a large ‘square’, twice as big as Hanover Square. Unusually for the time it was rectangular and described as a ‘garden’. The roads along each side continued beyond the square and thus eight streets join Grosvenor Square to the surrounding parts. The general plan of the estate was made by Thomas Barlow, a prominent carpenter and master-builder, in conjunction with the Grosvenor Estate manager and lawyer Robert Andrews. Both invested heavily in the new venture. The entire east side was leased by the builder John Simmons who erected a symmetrical terrace of houses, with a larger house in the centre, the block giving the impression of a palatial single building, perhaps the first such example in London. A modest chapel of ease was built in South Audley Street to a design similar to many in New England but no market was included in the development, presumably because of the close proximity of Shepherd Market.

Hanover Square was a development by Whigs and for Whigs. In contrast, the Cavendish-Harley development on the north side of Oxford Street was created by and for Tories. Edward Harley, son of Robert Harley, Lord Oxford, the leading politician under Queen Anne, married Henrietta Cavendish, daughter of the Duke of Newcastle. Together they owned part of Marylebone Fields, bordered to the north by Crown land (later to become Regent’s Park) and to the south by Oxford Street. As the Hanover Square scheme was being developed to the south, they saw an opportunity to develop their land on the opposite side of Oxford Street. In order to do so they canvassed those amongst their aristocratic and political Tory friends with a view to taking leases on plots to develop housing and build grand mansions.

In 1719 the surveyor John Prince drew up a general plan that included a square, streets, market and church. James Gibbs was employed to supervise the architecture and Charles Bridgman to lay out Cavendish Square, both of whom were members of the Harley circle of Tory associates. The various street names, such as Henrietta, Margaret, Welbeck and Wimpole were either family members or their country estates.

In order to forestall any competition, the market was the first section to be created. The Oxford Market was contained within a square building designed by James Gibbs and opened in 1720. It was located at Market Place, immediately to the north of Oxford Street and east of Portland Street. (It was enlarged over the following century and a half but demolished in 1880, although the surrounding street plan still exists). Gibbs also designed the church, which was built in 1724 and was fitted out by the same craftsmen who were later responsible for the interior of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. It was originally known as the Oxford Chapel but later renamed St. Peter’s, Vere Street. (It still stands in Chapel Place and Henrietta Place, in the shadows of Oxford Street’s department stores, and gives a good idea of the style of houses that originally surrounded it).

The Dukes of Chandos and Norfolk and Baron Bingley leased plots around Cavendish Square. Various financial problems, such as the collapse of the South Sea Company, changed and delayed plans and the square was slowly populated by houses in a piece-meal fashion. It was never quite as grand as originally envisaged, partly because the landed aristocracy preferred to spend their money on palatial houses on country estates they owned rather than plots of land they merely leased.

It was also the case that the market for palatial London homes in fashionable squares was somewhat exhausted by then, with aristocrats having a choice of Bloomsbury, Hanover, Grosvenor and Cavendish Squares. No new squares or major developments took place in the 1730s, although the gardener Thomas Huddle began building along the north side of Oxford Street, on the Berners Estate to the north of Soho.