The Regent’s Canal

The latter decades of the 18th century were the golden age of England’s canals and a network was created across the industrial heartland of the English Midlands. It finally reached the London area, at Paddington, in 1801. It would be another 19 years before a new canal was created to bring goods directly to the City of London, one of the last of the canal age.

A horse-drawn narrowboat owned by the Pickford company passes under Macclesfield Bridge, named after the Earl of Macclesfield, then Chairman of the Regent’s Canal Company. The bridge carries the northern entrance to Regent’s Park over the waterway. In 1874 it was demolished when a steam-powered boat exploded while towing a train of narrowboats carrying petroleum and gunpowder. The bridge was rebuilt and gained its nickname of ‘Blow-Up Bridge’.

During the 18th century Britain was undergoing what we call the ‘Industrial Revolution’. New inventions and techniques improved manufacturing and farming. The country’s roads were still in a poor state but raw materials, goods and produce had to be somehow transported as efficiently and safely as possible to and from places of manufacture and ports and markets. The solution was found in water transport.

Rivers in England had been canalized since the 16th century to assist the navigation of barges. Artificial channels were dug in order that short-cuts could be created where a river looped, or to smooth any rapid change in a river’s descent. In these cases the channel was fed by water from the river and is called a ‘navigation’. A notable example is the River Lea from Hertfordshire to the Thames, where a navigation was created, with the country’s first mitred lock gates introduced in 1571.

In 1761 the Duke of Bridgewater opened the country’s first waterway that was entirely canalized and did not follow the route of a river, known as the Bridgewater Canal. Its purpose was to transport coal directly from the Duke’s mines at Worsley in Lancashire into Manchester. The engineer for the project was James Brindley and he then proposed further canals that would link up the new industrial centres of the Midlands to the ports around the coast at Liverpool, Hull, Bristol and London. The Trent & Mersey Canal received Royal Ascent in 1766. Brindley’s Birmingham Canal followed between 1768 and 1772, connecting with the Staffordshire & Worcester Canal, which linked the Trent & Mersey Canal to the River Severn (and thereby Bristol) in 1772. After Brindley’s death the opening of the Coventry Canal and the Oxford Canal linked the Midlands to the River Thames in 1790. Brindley’s original idea, to be able to carry goods by barge from the industrial Midlands to any of the four major English ports, was thus realised.

All these waterways during Brindley’s lifetime were narrow canals, with locks and bridges built to fit ‘narrowboats’ of seven-feet wide and 72 feet in length. They also followed the contours of the land in order to reduce the number of locks (and the associated building cost), and they therefore wound in loops through the countryside. New canals dug after 1800 tended to be built to a wider gauge, permitting either two seven-feet wide narrowboats to fit into locks together or for a double-width barge. New techniques in building aqueducts and tunnels also allowed the later canals to be made straighter, reducing journey times.

With the opening of the Oxford Canal it was possible to transport goods all the way from the Midlands and beyond by water to London via the Thames. The locks on the Oxford Canal were only capable of taking one narrowboat at a time, however, and the canal itself looped endlessly through the countryside, with very slow journey times. From Oxford, goods had to be transferred onto larger barges for onward passage on the Thames.

At the end of the 18th century a new route was planned from Birmingham to the Thames at Brentford. At 90 miles in length, the Grand Junction Canal would more directly link London with the canal network of the industrial Midlands. A branch was created off the Grand Junction Canal at Southhall, leading to Paddington, which in those days was on the outskirts of the west of London. Not only did the Grand Junction cut 60 miles off the length of the journey to London, but it was also built with double-sized locks, so two narrowboats, or one wide barge, could fit into a lock, which greatly speeded up navigation. The Paddington arm of the Grand Junction terminated just to the west of London, in a large canal basin at the New Road (the Marylebone Road) and opened with great celebration in 1801.

As soon as the Grand Junction was opened a proposal was made by Thomas Homer, who owned a fleet of coal boats, and Sir Christopher Baynes of Harefield, to cut a new canal from Paddington. The ‘London Canal’ was to pass eastwards through the fields to the north of the New Road, then around the north and east of the City. The new venture would avoid the necessity to transfer goods onto wagons to transport them into the City from Paddington, as well as to the recently opened West India Docks to the east of London.

The new canal was to connect with the Grand Junction at Paddington. However, the directors of the existing canal would not agree to allow water to pass from the Grand Junction to the London Canal. Finding a source of water remained an unresolved issue so no progress was made on the scheme for a decade. Then in 1811 Homer heard of John Nash’s plans to develop Marylebone Park (later renamed Regent’s Park). He made a proposal to Nash for the latter to take charge of the construction of the canal, to pass through the park.

Nash obtained approval from the Prince Regent for the navigation to be called ‘The Regent’s Canal’. The Regent’s Canal Company was formed and Nash and his assistant, James Morgan, were thereupon engaged to oversee the canal’s creation. At the same time they were employed as civil servants to ensure it was completed according to the wishes of Parliament and in the best interests of the park, a conflict of interest which would be unthinkable in modern times.

There was much opposition to the proposed canal. Perhaps the most serious was from Edward Berkeley Portman. He owned an extensive estate at Marylebone through which the route would pass, and that required its line to be moved northwards. That then necessitated having to pay Thomas Lord the sum of £4,000 to relocate his cricket ground to its present position at St. John’s Wood. Various concessions had to also be made to landowners, including Henry Samuel Eyre, Lord Southampton and Lord Camden, including the provision of bridges.

Nash envisaged a scenic waterway passing through Marylebone Park and feeding an ornamental lake. When the park’s commissioners realized that cargo boats might spoil the tranquillity of the park’s residents in their grand villas he changed his plan. Instead, it would pass along the northern boundary of the park, hidden in a deep cutting and never feeding the lake. (The lake is actually fed by the River Tyburn, which passes through it).

In giving approval for the canal to pass along the northern boundary of Marylebone Park, its commissioners stipulated that a branch should supply markets on Crown-owned land to the east of the new Regent’s Park. For that purpose an Act was passed in April 1813 and a section of the canal was created, known as the Cumberland Market Branch. As the main line of the canal took a sharp turn from Regent’s Park north to Hampstead Road at Camden the branch would curve south-east down to the Cumberland and Clarence markets. (The branch and terminal basins lasted until the 1940s when they were filled-in with bomb-damage rubble).

After debate in Parliament, the Regent’s Canal Act was passed in July 1812, incorporating a wide range of details such as financial arrangements, where the water could and could not be taken to feed the canal, how much could be charged for freight carried, and a fine for anyone caught swimming in the water. The process of acquiring the necessary land went ahead, held up for a time by lengthy negotiations with the barrister Willam Agar, who had purchased the Manor of Pancras in 1810 and held out to gain the maximum remuneration. The Earl of Stanhope took on the role of mediator between Agar and the company until, after much legal action, agreement appeared to have been reached. Nevertheless, Agar’s intransigence at every step continued to be an expensive thorn in the company’s side throughout the period of construction and into the 1830s.

Neither Nash nor Homer had any experience of cutting a canal and the necessary tunnels, so a search for an engineer began by means of an advertisement. The advice of John Rennie, successful architect of docks, bridges and canals, was sought but he declined to be involved, perhaps because of his recent problems with a road tunnel at Highgate. When no-one came forward the task was given to James Morgan, on a salary of £1000. Work began in October 1812. Day-to-day affairs were handled by Morgan and several sub-committees of directors. Nash continued his involvement in the project throughout its early years when he and his wife were the largest shareholders.

In 1815 it was discovered that Homer had been embezzling company funds and he initially fled to Belgium. He was then apprehended in Scotland and sentenced to seven years transportation. The problem caused a shortfall in the company’s funds resulting in a temporary halt to the work while capital was raised.

The entire lock-free stretch from Paddington, through Regent’s Park to Hampstead Road at Camden, including the Maida Vale Tunnel, was completed and opened for traffic on the birthday of the Prince Regent in August 1816. To do so, the company came to a temporary agreement with the Grand Junction Company to supply the water.

During the early part of the 19th century the poet Lord Byron wished the area around the junction of the Grand Junction and Regent’s Canal at Paddington could be more like Venice. In the 1950s Byron’s thought was revived by the local council and the area took on the name of ‘Little Venice’. A large pool of water makes up the junction, with a small island in its centre. This became known as ‘Browning’s Pool’ after the Victorian-era poet Robert Browning who in the 1860s lived overlooking it.

One of the biggest challenges in the building of the waterway was in passing Islington Hill. It was decided to dig cuttings on either side of the hill and then a tunnel, from under the White Conduit House on the eastern side to close to the Rosemarie Branch inn on the western side. The underground section was (and remains) 960 yards long, passing under the new suburb of Pentonville, Islington, and the New River. Over four million bricks were used to line the tunnel and it was completed in September 1818. Landowner William Horsfall also created a 150-yard-long private basin at Battle Bridge (what later became Kings Cross), using spoil created by the excavation of the Islington Tunnel. In time this became known as Battlebridge Basin.

In the original plans for the canal a branch had been included for goods destined for the City, stretching from Canonbury Road Bridge at Shoreditch and passing south towards Aske Street where it would terminate in a basin. The terms from landowners were found to be excessive, however, and instead a basin was created off the canal to the east of Islington Tunnel. The basin extended south beyond City Road, which was bridged across it. Being close to the City of London the basin became very busy after the canal opened and soon eclipsed Paddington in the amount of goods trans-shipped.

At the eastern end of the canal at Limehouse a small dock was to be built with a tide lock, where barges could pass to and from the Thames. By 1818 it was agreed to make the dock and lock large enough for ships to enter from the river and thus bring additional revenue. The experienced dock engineer James Walker acted as a consultant. Tolls from collier ships bringing coal into the Regent’s Canal Dock, as well as ships operating short routes to Northern Europe, became a substantial part of the company’s operations and revenue. Some of the coal continued along the canal but much of it was trans-shipped by barge to factories and power stations along the Thames.

It was only in 1818 that a final decision was made regarding the design of the locks on the canal’s descent from Camden to Limehouse. They were to be the same size as that on the Grand Junction Canal, and thus accommodate one wide barge or two narrowboats. However, they were to be doubled up, with one lock beside the other. That provided the advantage of saving water in situations where a lock could be emptied into the one adjacent instead of running off into the pound below.

By March 1820 work on the entire canal was near completion, so the company began the process of employing toll-clerks, lock-keepers, and a dock-master at Limehouse. In the following months houses were constructed for them at their places of work. A general office was opened in Great Russell Street in Bloomsbury, moving in 1836 to City Road.

The entire canal was opened in August 1820 in a ceremony in which John Nash, James Morgan, and the company directors and shareholders travelled in a convoy of barges, including the City State Barge, from Horsfall Basin at Battlebridge to the sound of military bands, passing waving crowds. Arriving at Regent’s Canal Dock at Limehouse, they passed through the ship lock, and upriver along the Thames to Custom House. A banquet was then held at the London Tavern, the traditional venue for such events.

The completed waterway was eight and a half miles in length between Paddington to Limehouse, dropping 86 feet during its course. To travel from one end to the other boats must pass through 12 locks between Hampstead Road at Camden and Limehouse (with the stretch from Camden to Paddington on one level and thus lock-free). At the time of its completion the canal passed under 37 bridges, most of which were named after the owner of the land though which the canal passed, with William Agar as a notable exception. A bridge in the Regent’s Park section was named Macclesfield Bridge in honour of the company’s chairman, the Earl of Macclesfield, who had done much to ensure the venture came to fruition.

Canals are artificial waterways and therefore need to be fed with water at the same rate as its locks are filled and emptied. The Regent’s Canal Act of 1812 stipulated where it could not take its water from, which, crucially, included the adjoining Grand Junction Canal. To prevent water passing from one waterway to the other a stop-lock was built at the entrance to the Regent’s Canal at the Paddington end, with water in the Regent’s Canal to be kept six inches higher than that of the Grand Junction. The Regent’s Canal Company also had to provide a lock house for a supervisor to be employed by the GJCC but paid by the Regent’s.

Various options were considered for a supply, particularly pumping water up from the Thames. At a very early stage, the Regent’s Canal Company purchased over 100 acres of Finchley Common in the hope that enough spring-water could be drained off and channeled on a winding course from there to the canal at Chalk Farm via Hackney. By taking measurements they soon realized that the springs produced insufficient water for their needs and that land was sold off.

During 1815 and 1816 the company also experimented at Hampstead Road with a water-saving method using a ‘hydro-pneumatic’ lock. It had been devised by Colonel (later Sir) William Congrave, best known for his rockets that were used in the Napoleonic Wars. After much effort the company decided that the system was unreliable so abandoned the idea.

One of the reasons the Grand Junction Canal Company were unable to initially provide a supply on a permanent basis was that they were contracted to provide water to its subsidiary, the Grand Junction Water Works Company, an enterprise that supplied water to residents of West London. A solution was found whereby the Regent’s Canal Company was to provide an alternative supply to the GJWWC by pumping from the Thames at Chelsea. Thus, the GJCC were then able to supply water for the Regent’s Canal and in the same agreement the Regent’s took over reservoirs at Ruislip, and at Aldenham near Watford.

These arrangements were initially satisfactory but during the 1820s traffic on the Regent’s Canal increased, with a growing use of water. Then there were droughts in 1833 and 1834. It prompted the company to purchase over 130 acres of land to create a reservoir close to the Welsh Harp Inn at Brent, which could be fed by the Silk Stream and Dollis Brook. The reservoir was completed in 1838 and extended further in 1853.

The Regent’s Canal was soon busy with waterborne traffic, with vessels carrying a wide variety of goods including coal and coke, sand, road-building materials, bricks and slates, iron, lime, timber, stone, chalk, salt, ice, and manure. Businesses were established alongside the canal to take advantage of water transport. Some created lay-bys to prevent their boats blocking the canal while loading and unloading. Several companies moved from Paddington Basin to City Road Basin to be closer to the City. One of those was Pickfords, the important nationwide carrier and barge operator with a fleet of 80 narrowboats, who in 1820 moved their warehouse from Paddington Basin.

In 1819 the Gas Light & Coke Company, which supplied gas to the City, Westminster and Southwark, began using a wharf at City Road Basin to receive coal supplies. The Imperial Gas Light & Coke Company was formed in 1821, creating gasworks beside the canal at St. Pancras and Haggerston, and other gas companies followed their lead.

By the time the Paddington to Hampstead Road section opened in 1816 the company had created two basins at Hampstead Road, which were let out to traders. John Nash leased the wharves around Regent’s Park Basin at the end of the Cumberland Market Branch and in 1830 a hay market was opened there. Regent’s Canal director John Edwards created a private basin in parallel to City Road Basin, which opened as Wenlock Basin in 1826 and extended several years later. (From 1850 the Grand Junction Canal Company used the basin for boat-building). Other private basins were created in Hackney at Kingsland Road and Cambridge Heath Road. The first ship entered the Regent’s Canal Basin at Limehouse in 1820 and in the 1830s over 500 ships were using the dock each year.

Sir George Duckett created the Hertford Union Canal, linking the Regent’s Canal at Bethnal Green to the River Lea at Hackney Wick. It was intended to allow boats to pass between the two waterways without navigating the tidal Bow Creek and Thames. It opened in 1830 but was insufficiently used to make a profit and in 1832 Duckett was declared bankrupt. The Regent’s Canal Company acquired the Hertford Union in 1854 when it was put up for auction.

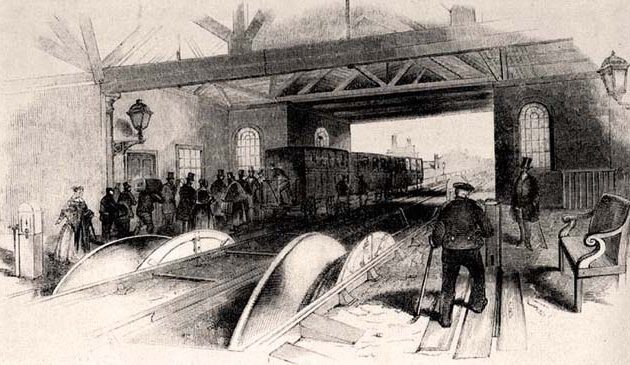

In the early days of the canals, boats were pulled by horses that walked along the path at the side of the canal. Both narrowboats and wide barges used the canal. The two tunnels at Maida Vale and Islington were cut without a towing path so boats had to be ‘legged’ through; a method where two bargees lie on their backs, each on a board fixed to the side of the boat, walking along the wall of the tunnel to propel the boat forward. It is a slow process and caused bottlenecks, especially at the lengthy Islington tunnel. From 1823 the company undertook several experiments to tow boats through the tunnel and a steam-powered tug was introduced that could pull itself along a chain and haul up to four vessels at a time.

The total cost of creating the canal to March 1829 was over £870,000, more than twice the original estimate. The Regent’s Canal Company struggled financially during the years of construction and in the early years of operation but was finally able to reward its long-suffering shareholders from 1829 with a small dividend. By the mid-1820s the Regent’s Canal Company was achieving annual revenues of around £25,000 and over £80,000 in the 1870s.

In 1837 Robert Stephenson’s London & Birmingham Railway opened, following the route of the Grand Junction from the Midlands, passing over the Regent’s Canal at Camden on its way into Euston Square. Much of the materials for building the line were delivered by boat along the Regent’s Canal and the Regent’s Canal Company also contracted to supply water for the steam locomotives. Camden became a trans-shipment point between rail and barge and in 1841 Pickfords opened a basin and depot there.

The Eastern Counties Railway opened in 1839 from Shoreditch to Norwich, crossing the canal at Mile End. Then in 1840 the London & Blackwall Railway opened, crossing over Commercial Road lock and along the northern side of the Regent’s Canal Dock by way of a viaduct. The Great Northern Railway arrived in 1852, eventually passing under the canal by tunnel on its last stretch into Kings Cross. The GNR then built the large Granary warehouse on the north side of the canal, with canal basins below. In 1868 the Midland Railway passed over the canal into St. Pancras Station. The Great Central Railway opened in 1891, crossing the canal near Lisson Grove into its terminus at Marylebone. The railway company created the Regent’s Canal Wharf trans-shipment depot.

Railways were much faster and more efficient and soon began taking long-distance freight traffic away from the canals, although the canals gained additional business in the carrying of coal, often used to power the steam trains. In the mid-19th century companies such as Pickfords gave up carrying by barge to operate primarily as agents for railways.

For the Regent’s Canal perhaps the most significant competitor was the North London Railway, which opened in 1851 from the goods yards at Camden to Bow. It allowed goods to pass speedily from the Midlands to the London docks, avoiding altogether the much slower Grand Junction and Regent’s canals.

As early as 1835 there were plans to fill-in the canal and build a railway over it, but they eventually came to nothing. In the early 1880s the Regent’s Canal City & Docks Railway Company was formed to operate both a railway network and the Regent’s Canal. It acquired the canal in 1883 but eventually dropped its plans for the railways and in 1900 the company was renamed the Regent’s Canal & Dock Company.

Coal traffic decreased during the early decades of the 20th century, particularly with the opening of the large Beckton Gas Works on the Thames. The business was replaced, however, by supplying electricity generating stations along the canal.

In 1928 the Regent’s Canal Company acquired several canals in the Midlands and at the same time merged with the Grand Junction Canal Company to form the Grand Union Canal network. In 1932 several more Midlands canals were acquired. The company by then had expanded its network of canals from the original eight miles of Regent’s Canal to a network of almost 280 miles, stretching from London to Birmingham, Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire.

In January 1948 the Grand Union Canal network was nationalized, becoming part of the British Transport Commission. It then transferred in 1963 to the government-owned British Waterways Board. By then competition from road and rail had severely reduced commercial traffic on the network. In 1973 commercial carrying on the Regent’s Canal ended and shipping at the Regent’s Canal Dock largely ceased in the 1980s.

In 1951 a trip-boat service began along the Regent’s Canal and BWB established a successful waterbus service between Little Venice and London Zoo. Private moorings for pleasure boats began to be set up along the canal. A cruising club was established at St. Pancras, and Regent’s Canal Dock became a marina. The main users of City Road Basin since 1970 have been a boat club, and in 1977 the Pirate’s Castle community centre opened over the canal at Camden. The busy Camden Market has developed around Hampstead Road Lock. Battlebridge Basin has been a mooring for residential narrowboats since the 1970s and in 1992 the London Canal Museum opened there.

During the 20th century some of the basins along the Regent’s Canal have been filled in or reduced in size and most of the commercial and industrial buildings along its banks have disappeared. Yet the main part of the route of the canal remains and now makes for a pleasant walk or boat trip.

< Go back to The Age of Improvement or to Transport >

Sources include:

- Alan Faulkner ‘The Regent’s Canal

- Michael Essex-Lopresti ‘Exploring the Regent’s Canal’

- David Fathers ‘The Regent’s Canal’