London’s Jewish Community in the 19th century. Part 2 – Their lives

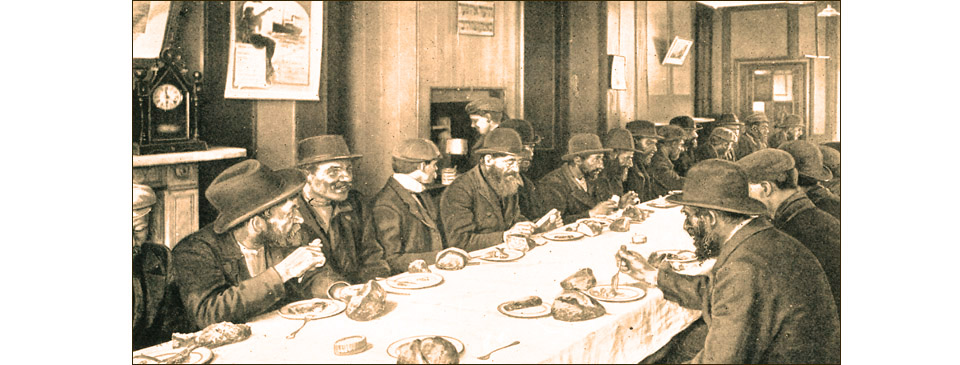

Newly-arrived men are provided with a frugal meal at the Poor Jew’s Temporary Shelter in around 1885. It began in Church Lane, Whitechapel. Sir Samuel Montagu and others took it over and provided a building in Leman Street to give a home for new arrivals for up to two weeks. It eventually sheltered up to 4,000 immigrants each year.

In the minds of many British Gentiles the stereotype Jew was a peddler of goods, often engaged in nefarious practices. ‘To jew’ became a verb meaning to swindle. In the latter 18th century the London magistrate Patrick Colquhoun wrote of the Ashkenazim: “[they] establish a system of mischievous intercourse…all the better to carry out their fraudulent designs in the circulation of base money, the sale of stolen goods…as well as other items pilfered from the Dockyards”. It was a view that persisted. Charles Dickens cast Fagin the Jew as a criminal in his novel Oliver Twist, published between 1837 and 1839. Even several Jewish novelists wrote works in which Jews were the wrongdoers. When Jack the Ripper’s murders began to take place in Whitechapel in 1888 fingers were quick to point at the Jewish community. It was far from the truth. Most were honest, peaceful, law-abiding, industrious, thrifty, and never intoxicated.

Kosher laws define what types of food are fit for Jews to eat, how animals should be slaughtered, and how food show be prepared. The supply of food is overseen by the London Board for Shechita, which was formed in 1804 and continues as a non-profit making charity. A cluster of kosher butchers shops served clients around the junction of Middlesex Street and Wentworth Street. If a market stall was found to be selling non-kosher meat the Board would post notices around the streets to warn Jews.

Ashkenazi Jews brought to Britain a variety of types of food that have become staples of the British diet, including fried fish (which, when joined with fried potatoes has become fish and chips). One theory is that Britain’s first fish and chip shop was that of Joseph Malins in Old Ford Road, Bethnal Green, opened in 1860. Many fish and chip shops in London continued to have Jewish owners well into the 20th century. Other food assimilated into British cuisine includes smoked salmon, beigels (bagels), pickled gherkins, and cream cheese.

Jewish charity was extensive in London, including the Shabbat Meals Society, the Soup Kitchen for the Jewish Poor at Spitalfields, the Jews’ Hospital (originally at Mile End but later moving to Norwood), the Jewish Lodging House in Gun Street, Spitalfields and the Jew’s Orphan Asylum in Leman Street. There were numerous Jewish societies for the benefit of their members, particularly to distribute death benefits. The Jewish Working Men’s Club in Great Alie Street near Aldgate was founded largely by Samuel Montague in 1876.

Various organisations also emerged to ensure that Jewish youths remained occupied and away from temptation. The quasi-military Jewish Lads’ Brigade was established in 1985 in the East End by an army officer and could often be seen marching through London’s streets. The following year the Brady Street Club began as a non-denominational club for boys but evolved into a Jewish organisation. Other clubs followed but almost all exclusively for boys. Athletics was a principle point of interest but it was impossible to compete against non-Jewish clubs, which played matches on Saturdays, the Jewish Sabbath.

Jewish children tended to be well-schooled, even before the introduction of state schools. The Spanish & Portuguese School had been in existence beside the Bevis Marks synagogue since the 17th century. The Westminster Jews’ Free School was founded in 1820 as part of the West Synagogue on the Stand. The most pre-eminent of these voluntary schools was the Jews’ Free School at Spitalfields, opened in 1817 and supported by the Rothschilds. At the end of the century it was the largest elementary school in England, with around 4,300 pupils, both boys and girls. The headmaster for 51 years from 1819 was Moses Angel. However, the education given was quite alien to many who arrived with the great wave of East European immigrants. They had mostly been taught in one-room schoolhouses in their homelands, often the house of the schoolmaster, where they had learnt Bible, prayer, religious matters, and Yiddish. In 1870 Moses said of the children of recent immigrants: “Many of them scarcely knew their own names” and they “knew neither English nor any intelligible language”.

Other schools founded in the 19th century included the Stepney Jewish School at Stepney Green. Following the Education Act of 1870 these voluntary schools were funded by the government and their curricula became more Anglicized. There was then less need for parents to send their children to a specialist Jewish school, although at the end of the century 16 state schools in the East End were primarily Jewish, and another seven English schools had a high percentage of Jewish children. It was noted that Jewish pupils had, on the whole, a better sense of morals and commercial understanding than English children. Outside of class hours many boys also attended a heder, an unofficial class, where they were taught Bible, prayer, and Jewish law. By the end of the century there were at least 200 hadarim in the East End.