The medieval Westminster Abbey

In an attempt to add to the prestige of Westminster Abbey Henry III acquired from the Patriarch of Jerusalem a crystalline reliquary of Christ’s blood, together with a letter of authentication. On St. Edward’s Day 1247 Henry carried the reliquary from St. Paul’s Cathedral to Westminster Abbey, dressed in a humble cloak, and in procession with all the priests of London. The monk Matthew Paris, who witnessed the procession, recorded it in his manuscript Chronica Maiora, a detail of which is shown here.

Westminster Abbey had been transformed in the 11th century from a minor Benedictine monastery into a major Romanesque building, of the type observed by Edward the Confessor in France. Two centuries later Henry III was to begin yet another transformation of the abbey based on the then fashionable style. It has left us with a unique mixture of French and English Gothic.

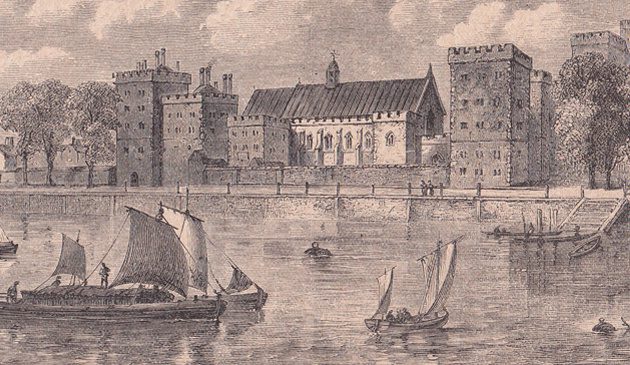

The Benedictine abbey of St. Peter was probably founded by Dunstan in around 960 on an island formed where two branches of the River Tyburn flowed into the Thames, about a mile west of London. King Cnut built a small palace on the island beside the monastery. The abbey became known as the ‘west minster’, and the royal palace as the Palace of Westminster. King Edward transformed the small abbey into a great Romanesque building, where he was buried in January 1066. The following day the first coronation to take place in the abbey was that of Harold II, followed at the end of that year by William the Conqueror. Since then, every coronation of an English monarch has taken place in Westminster Abbey.

A notable abbot at Westminster during the early medieval period was Gilbert Crispin. He originated in Bec in Normandy, where his parents were devoted to that abbey. The Archbishop of Canterbury, Lefranc, who will have known the parents from his time at Bec, brought Gilbert to England in about 1080. Gilbert was elevated to become the Abbot of Westminster in 1085, where he remained until his death in 1117 at a considerable age. He came to England at around the same time as the Jewish community of Rouen who settled in London and one of his famous writings is his Dialogue between a Christian and a Jew based on a discussion Gilbert had with a learned Jew. At a time when Jews were being persecuted based on perceived instructions from the Pope, Gilbert showed a kindly attitude to his Jewish friend.

Gilbert’s successor at Westminster, Herbert, was less capable and the abbey began to fall on hard times. In medieval Europe nothing enhanced the prestige of a town or religious establishment as much as being the home to the remains of a saint. It was during Herbert’s time, in the 1120s, that Westminster’s clerks began forging ancient documents to enhance the abbey’s history and this practice continued under his successor, Gervase of Blois.

The deceits reached a peak in the mid-12th century under the prior Osbert de Clare. To Osbert the abbey was the centre of the world, where God had chosen to dwell, surrounded by a Babylonian hell in the outside world. In seeking ways to increase the status and independence of the abbey he set about re-writing its early history, exaggerating King Edward’s piousness and creating new stories of miracles. Osbert’s principle aims were the canonisation of Edward, to ensure St. Peter’s remained as a grand royal chapel where coronations and the burial of monarchs would continue forevermore, and to be exempt from control of any bishops. It was necessary to convince the Pope and the King and to do so the Life of St Edward, a bogus biography, was produced in 1138. Forgers were also employed to create apparently ancient royal and papal proclamations detailing fictitious privileges from St. Dunstan, King Edgar and other popes and kings, this being fairly common practice by monasteries throughout Europe at the time.

For many years there had been stories of miracles surrounding the grave of Edward at Westminster Abbey. The pastoral staff of the Saxon Bishop of Worcester was said to have rooted in the stone of Edward’s tomb until the dead king assured him of his bishopric. A blind beggar and a hunchback were believed to have been cured. According to the later account by Osbert, in 1102 it was decided to open Edward’s tomb in the presence of King Henry I, Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester, and Abbot Crispin. When the slab was removed the body inside was found to be whole and intact, not decomposed.

Ironically, despite his duplicity, Osbert was never able to achieve his objective. He led a delegation to Rome in about 1138 but his request for canonisation was declined by Pope Innocent II. It was in the time of the more scrupulous and diplomatic abbot, Master Laurence, that events converged for Edward to be duly canonised. It was certainly in the interests of the monarch for that to take place because having a saint in the royal line would elevate the conception of kingship. Henry II had backed Alexander III as the new pope, and in return Alexander agreed to Henry’s request for Edward’s canonisation. A ceremony was held at the abbey in 1163 attended by the King and Archbishop Thomas á Becket. Edward’s body was lifted from its grave and placed in a new coffin, which was transferred to a tomb in the same position as before but above ground. That day, 13th October was thereafter the Feast of St. Edward the Confessor.