The Thames Tunnel

The opening ceremony of the Thames Tunnel on 25th March 1843. The procession walked through the tunnel from Rotherhithe to Wapping on one of the carriageways and then back to Rotherhithe on the other carriageway. Marc Brunel (on left holding his hat) acknowledges the cheering of well-wishers.

Unlike Dodd’s, Vazie’s and Trevithick’s earlier attempts, it was not the end of the story for the Thames Tunnel. The government rescued the project with a loan of £246,000. A new, improved, and larger tunneling shield was installed. Work resumed in March 1835 and continued despite further floods in August and November 1837 and March 1838. Boring began at the Wapping end in June 1840. By March 1843, twenty years after Marc Brunel embarked on the project, work on the 1,200-feet long tunnel was complete. It consisted of two parallel carriageways (referred to as “archways”) linked by alcoves, each wide enough for a carriage, together with footpaths. It was lit by gas, which also kept the tunnel warm. The combined width of the two carriageways was 38 feet. Seven and a half million bricks had been used to line the tunnel.

A grand opening ceremony was held, attended by dignitaries including the Lord Mayor of London, and scientists and architects including John Rennie and Michael Faraday. A notable absentee was Brunel’s great supporter, the Duke of Wellington, who was otherwise engaged. In the first 27 hours, 50,000 people paid to walk through the tunnel. After its opening it became London’s greatest attraction. Within 15 weeks a million pedestrians had paid one penny each to walk through, two million in the first year, equivalent to almost the entire population of London. In July Queen Victoria arrived by royal barge, walked through the tunnel, and honoured Marc Brunel with a knighthood at the suggestion of Prince Albert who had shown great interest in the project. On the first anniversary of the opening a three-day fair was held in the tunnel, attended by 66,000 people, and that continued every spring. Grand fairs with many attractions continued. It was particularly popular in 1851, the year of the Great Exhibition that brought thousands to London.

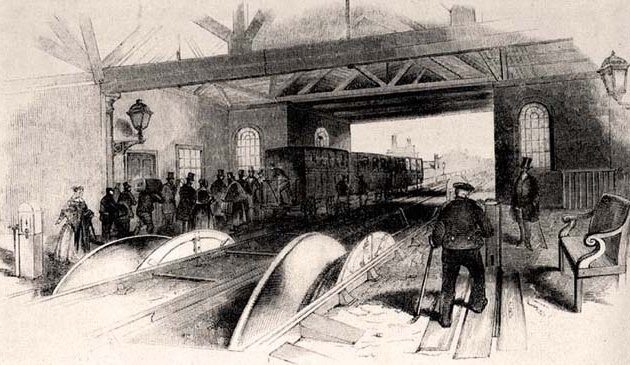

The original plan was for the tunnel to be accessible to horses and carriages but was initially only accessible to pedestrians descending the shafts at either end by steep stairs. It was so deep under the river that impossibly long approach roads would have been necessary for horses to make the descent. In its report at the time of opening, the Illustrated London News stated: “The carriage-ways have yet to be constructed: each will consist of an immense spiral road, 200 feet in diameter, winding twice round a circular excavation, 57 feet deep, in order to reach the proper level; the road itself being 40 feet wide, and the descent very moderate.” The original estimate in 1823 to complete the work was £160,000. In 1843 this had risen to over £400,000, with a further £200,000 required to construct the roadways at either end, a total of £614,000. The roadways were never built, no facilities for horses and carriages were ever added and thus the tunnel’s value for crossing the Thames remained limited. Within the first year it became clear it would not be a commercial success and no dividends were paid to shareholders. Stalls and shops selling souvenirs were kept in alcoves along the tunnels. It was busy during the day but gained an unwanted reputation as a haunt of prostitution at night.

Marc Brunel suffered a series of strokes and never accepted any commissions of work after the completion of the tunnel, although he did assist his son on other projects. He died in 1849 at the age of eighty. Isambard became one of Britain’s greatest and best-know engineers. Some of his achievements include Paddington station and the Great Western Railway, the SS Great Britain (the largest ship afloat at that time), the even bigger SS Great Eastern (built at Millwall on the Isle of Dogs) and the Clifton Suspension Bridge at Bristol. He died in 1859, ten years after his father and aged just 53, and five years before the opening of the suspension bridge. Marc, Sophia and Isambard were all buried in the family plot at Kensal Green cemetery.

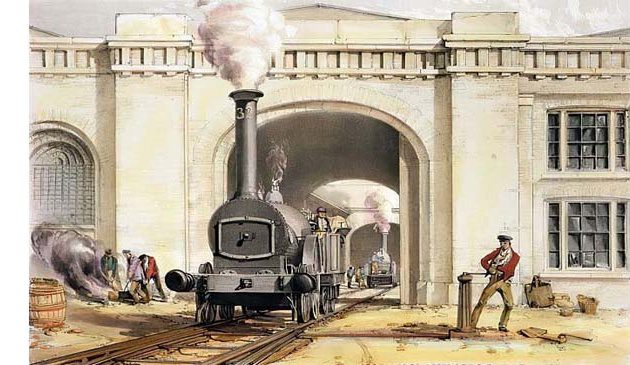

With little income the Thames Tunnel Company’s funds dried up. In 1862 the tunnel was sold to the East London Railway Company for £200,000 for their New Cross to Wapping line, a substantial loss compared with the cost of construction. Steam train services ran through it in 1870, with Wapping and Rotherhithe stations at either end. It eventually became part of the London Underground and was electrified in 1913.

Ultimately the Thames Tunnel was a financial failure for its initial investors. Yet it was an engineering triumph and has now remained in use for the best part of two hundred years. The invention of the tunneling shield allowed for the creation of London’s extensive underground railway system, coal-mining under the sea in the north-east of England, as well as tunnels throughout the world. The Blackwall Tunnel was opened 50 years after the Thames Tunnel, finally carrying traffic under the river. A plaque at Wapping station states:

The tunnel which runs under the Thames from this station was the first tunnel for public traffic ever to be driven beneath a river. It was designed by Sir Marc Isambard Brunel 1769-1849 and completed in 1843. His son Isambard Kingdom Brunel 1806 -1859 was engineer-in-charge from 1825 to 1828.

The building that housed the tunnel’s steam pump at Rotherhithe opened as the Brunel Museum in 2006.

Sources include: John Pudney ‘Crossing London’s River’; Illustrated London News (1843); ‘Old & New London’ ed.Walter Thornbury (1897); www.the brunelmuseum.com; John Pudney ‘London’s Docks’.

< Back to Bridges and Tunnels