Whitehall Palace in the Stuart period

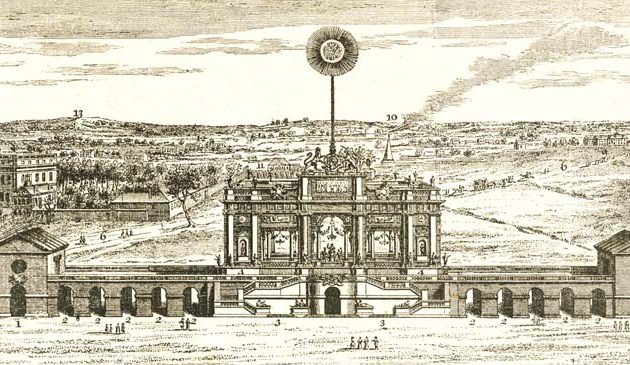

The Holbein Gate of the former Whitehall Palace, with the Banqueting House on the right, as they were in 1743 It is from a drawing by Thomas Sandby, who was employed as a draughtsman at the Tower of London. The gate was removed in 1759 and much of the material acquired by the Duke of Cumberland to be installed at Windsor Great Park under Sandby’s direction.

Charles I also hoped to transform Whitehall into a spectacular palace. During his reign the ceiling of the Banqueting House was decorated with a series of nine paintings by Peter Paul Rubens, which were installed in 1635. Charles knighted Rubens for his efforts. The cockpit, previously used for cock-fighting, was converted into a theatre by Inigo Jones, remaining octagonal and with a semi-circular stage. A timber-framed hall was built over the former Preaching Place. Masques were performed in both these places, as an alternative to the Banqueting House.

Charles had an uneasy relationship with Parliament. In January 1642 he attempted to storm the Commons and arrest six men, but they had been forewarned and hid in the City. The following day Charles sought them at the Guildhall but again without success. Four days later, fearing reprisals, the King left Whitehall. During the subsequent civil war Whitehall and the London area was under the control of the Parliamentarians.

In 1644 a Committee of Whitehall carried out a purge of any Royalists and papists who remained at the palace. In the same year the stained glass of the palace’s Chapel Royal was smashed and replaced with clear glass. Sculptures and pictures were defaced, the cross taken down, and the organ removed. In 1647 the nearby Eleanor Cross at Charing, which in modern times gives its name to the railway station, was demolished and some of its stones used as paving at Whitehall. The palace was used to house Parliamentary troops in 1648 and decorative hangings were sold to raise money for the army.

By 1646 Charles was taken prisoner by the Parliamentary side but even then he still entertained hopes for the rebuilding of Whitehall. While the King was being held at Carisbroke Castle on the Isle of Wight Jones and his colleague John Webb were summoned to discuss the possible rebuilding.

The captive Charles was brought to St. James’s Palace in January 1649, put on trial at Westminster Hall and sentenced to death. The warrant for his execution stated that he should be “putt to death by the severinge of his head from his body…In the open Streete before Whitehall”. On 30th January he was carried by sedan chair across St. James’s Park, and then over the Holbein Gate. An opening had been made in the Banqueting Hall through which he passed out to a stage erected in the street facing the Tilt Yard. Members of the public watched the beheading, some from the roofs or windows of adjoining houses. His body was placed in a room within the palace for the public to view in the following days.

After the execution, Parliament began to disperse the extensive royal art collection and many of the palace furnishings. Pictures of the late King were removed, gold and plate melted down, and jewels and the royal armour sold. (Many were returned during the reign of Charles II). Members of Parliament and officials moved into palace rooms and retained furniture for their own use. On a visit to Whitehall in 1656 John Evelyn noted that the palace was then “glorious and well furnished”.

During the Civil War Oliver Cromwell rose as a military and political leader on the Parliamentary side. After the execution of the King, Cromwell resided at the Cockpit within the palace. In 1653 he was appointed as Lord Protector, effectively the head of the nation and in April 1654 he moved from the Cockpit into the palace’s royal apartments. As with monarchs before and after, Cromwell lavishly entertained at Whitehall, including for officers of his army, members of the Commons, and ambassadors.

There were attempts to assassinate Cromwell during his time as Protector. One of those was at Whitehall in January 1656 when a plan to set the palace alight was thwarted. Cromwell died at Whitehall in September 1658, perhaps of influenza. A severe storm was raging at the time, with trees uprooted within St. James’s Park, which was taken as a sign by Cromwell’s enemies that the devil had come for him.

In 1659 Whitehall was offered for sale but in February 1660 General Monck and his Coldstream Guards marched into London, marking an end to the short republican period. Monck took up residence in the Prince’s Lodgings in the palace and later moved to the Cockpit Lodgings, where he died in 1670. A new Parliament ordered that the palace should be restored for the arrival of Charles II from exile. Inigo Jones had died in 1652 so John Webb was put in charge of the preparations. The new king was received by Parliament at Whitehall Palace in May 1660: the Commons in the Banqueting House and the Lords in the drawing room of the palace.

Back in 1630 the Lord High Chancellor, Sir Richard Weston, had commissioned from the sculptor Hubert le Sueur an equestrian statue of Charles I but it had yet to be erected before the outbreak of the Civil War. Parliament sold it to a brazier who claimed to have melted it down, selling parts of it as souvenirs to Royalists. In reality it had been hidden. In 1676 it was placed facing towards Parliament, at the point where those who had signed the King’s death warrant were executed in October 1660 following the restoration of Charles II. It remains there today.