Buckingham Palace

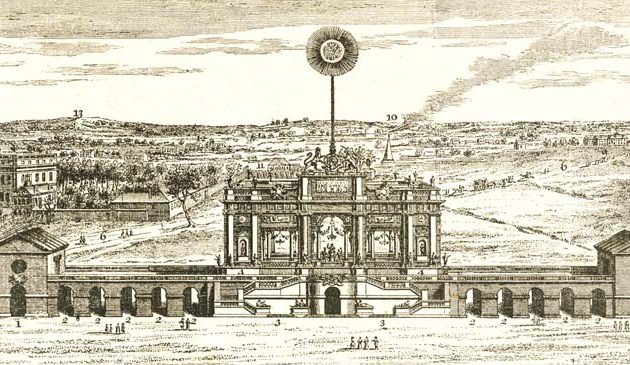

Buckingham House in 1775 after remodelling by Sir William Chambers for King George III. A mast on a roof to the left of the main building supported a weathervane connected to a wind dial over the chimneypiece in the library below. It enabled George to have an understanding of the movement of naval ships.

George III died in 1820 and the Prince Regent ascended the throne as George IV. In 1821 the new king’s favourite architect, John Nash, began drawing up plans to enlarge and remodel Buckingham House. The initial idea was that it should be a grand home for the King rather than a state palace.

Nash’s first plan was to enlarge the existing house, which was incorporated into the west wing of the palace and still remains part of the existing building. By 1825 the scheme had grown in scale to be a palatial national monument, including a triumphal entrance archway, the Marble Arch, to celebrate the victories over Napoleonic France. It would be the climax of Nash’s ‘Metropolitan Improvements’ that were transforming parts of London, which included Regent Street, Regent’s Park, and the Regent’s Canal. Buckingham Palace would be the first palace in the metropolitan area to rival Whitehall in the 17th century.

Carlton House was demolished and replaced with two rows of houses named Carlton House Terrace to raise funds for the additional work at Buckingham Palace. Although Nash was the primary architect, the opinions of the King and his artistic adviser Sir Charles Long were also prominent.

The work on Carlton House Terrace and Buckingham Palace also provided a stimulus to regenerate St. James’s Park. A great triumphal arch was created to form an entranceway from Kensington and Hyde Park, with a fine new screen entrance into the latter, both designed by Decimus Burton.

By June 1825 four hundred workmen were employed on site at the palace. George made continuous alterations to the plans, resulting in delays and increased costs. The change from being a family home to a palace where the King could hold court required the addition of a throne room and grander state rooms. The need for these, together with offices for the royal household, resulted in the building expanding into three sides of a square of equal height throughout, around a forecourt. The exterior was faced in Bath stone, detailed in French neo-classical.

Nash’s grand state rooms remain the principal internal features of the palace. In his ‘Mogul’ tent ceiling of the throne room he developed themes had had begun in his work for the Prince Regent at the Brighton Pavilion. Much of the internal plasterwork was by William Pitts. The frieze in the throne room and relief panels of the grand staircase are the design of the painter Thomas Strothard. Marble work was by Joseph Browne. Various craftsmen created the chimneypieces. Most of Nash’s state rooms in the main block still survive, with the exception of the picture gallery. Much of the furniture, chandeliers and works of art from Carlton House were moved into Buckingham Palace.

The Royal Mews, which still house the royal carriages and their horses, was designed by Nash. A domed semi-circular bow faced the garden at the rear. The garden, covering about 40 acres, was landscaped by William Townsend Aiton and the formal gardens by Henry Wise were largely removed. A five-acre lake was added.

By the summer of 1828 the cost of the enlargement of the palace had risen to nearly £300,000 but Nash insisted to Parliament that everything was under control. Yet a year later it had increased to nearly £500,000 with much work still to be completed. George died in 1830. Parliament launched an investigation into the costs and censured Nash for negligence. The following year he was dismissed from the project.

George was succeeded by his brother. William IV was a man of simple tastes who disliked Buckingham Palace and continued to live in his former home of Clarence House on the north side of St. James’s Park. He considered converting Buckingham Palace to a barracks but, with so much money already spent, the Prime Minister persuaded him to continue with the work but minimising further expenditure. The government took over the project and in 1831 Edward Blore, who had recently rebuilt the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Lambeth Palace, was commissioned to undertake the remainder of the project.

Blore was provided with a budget of £100,000 with a priority of financial control rather than architectural brilliance. While preserving the fine work of his predecessors he also made practical changes to offices, servants’ quarters and the kitchens. An attic storey was added for additional bedrooms. A low screen building was added on each side of the building to overcome one of the criticisms of Nash’s design, with the one on the south containing a guardhouse. William requested a state dining room on the principal floor, requiring the reconstruction of Nash’s music room. New apartments for the King and Queen were created in the north wing. Lord Duncannon took control of internal decoration, in consultation with William’s consort Queen Adelaide, while Blore worked on the main architecture. Some economies were made: the Marble Arch entrance was left unfinished according to the intended design, and remains so.

The work on the palace was completed during William’s reign but he never lived there. In October 1834 the Houses of Parliament were destroyed by fire and William hoped to offload the unwanted palace as its replacement. It was not to be, and MPs instead decided to rebuild the parliament building.